Lakewood residents may know Beck Center primarily for its arts education and theater programs. Across the parking lot, behind the main building, Beck Center offers a different set of music spaces. In one room, guitars line the wall, a gray drum kit occupies the corner. Tambourines and maracas compete for shelf-space with percussion instruments you’ve likely never heard of. This is the home of the music therapy program, which will be wrapping up its 30th year in existence this September.

What is music therapy? I didn’t know. So, I asked local experts. The question turned out to have no simple answer.

Michael Simile, a member of Beck Center’s arts therapy faculty since 2018, says, “I think music therapy is something that’s really hard to define. It’s so broad.”

Ronna S. Kaplan, who chaired the Music Settlement’s Center for Music Therapy until 2019, grappled with this same question. In an article published by Huffpost, Kaplan writes, “Music therapy means many different things to many different people, but common threads among definitions include the importance of music, relationships, developing clients’ or patients’ potentials and improving the quality of their lives.”

Andrea Vallejo Wead, current director of music therapy at the Music Settlement, emphasizes that music therapy differs for each client. “It’s very tailored to the individual, and that’s how we’re taught, is to look at individual goals and needs. So we’re trained in a variety of instruments and styles and things like that, so really, it’s just finding out what the individual client needs.”

She adds, however, that “there are a lot of commonalities between treatments. Because you could have someone who is in senior living, who loves the Beatles. You could have somebody in mental health who loves the Beatles.”

Tracy Ammon has worked in the Creative Arts Therapies program at Beck Center since 2008, and has overseen it as associate director since 2021. This year, she became director of education. What Ammon emphasizes is the emotional power of music itself and quotes Hans Christian Anderson.

“’Music speaks when words cannot.’ but it’s also a very non-threatening medium. Everybody is connected by music in some way. It can be a very motivating factor with children and adults alike.”

Seeing music therapy in person

One of Beck Center’s music therapy clients is Nikki, a young woman with Down syndrome whose favorite song is YMCA by The Village People. She is non-verbal and suffers from a number of health issues that cause her discomfort and pain. Nikki struggles, at times, to communicate what is hurting her, which leads to frustration. Gavin Dorsey, a Beck Center therapist, said his goal for Nikki’s sessions is to encourage meaningful engagement and participation during the session and, more recently, to motivate Nikki to practice using her alternative communication device.

I had the opportunity to observe one of Nikki’s therapy sessions. Dorsey focuses on instruments Nikki can play and has been most receptive to: an electronic Omnicord, which functions as a string instrument that can be played with one finger; a steel tongue drum, which releases a rich meditative tone when struck with a rubber-tipped mallet; and, due to Nikki’s musical background, a drum kit.

I watched as Dorsey and Maria, Nikki’s mother, went about trying to motivate her to learn the names of each instrument with her communication device. Nikki was unenthusiastic. Beyond her chronic pain, she had fallen and scraped her leg at school that same day, leading to a phone-call home and an early dismissal. Her bandwidth for participation was low.

I watched as Dorsey and Maria struggled to engage her with the music and memory exercises. More than once, Nikki cried and shouted in frustration and pain. It was the tongue drum that had the most noticeable effect. When Dorsey struck a note, the room filled with a soothing, resonant tamber. Nikki soon quieted and, with the help of her mom, struck a few notes.

Dorsey explained that the drum is therapeutic in helping Nikki manage her pain. “It helps to calm her. So using an instrument like this for music relaxation, it’s like a distracting stimuli, to distract them [her] from that pain or discomfort that they might be experiencing,” Dorsey said.

While many private music therapy sessions like Nikki’s focus on fulfilling specific therapeutic goals, others may focus, more generally, on creating spaces of support.

Graham, who is now 13 years old, has been coming to Beck Center since he was in kindergarten. Graham is interested in music and programming his own video games. He has a sensory processing difference, which his father Dan describes as a sensitivity to loud noises and, more generally, a heightened or lowered experience of the senses — textures in food or clothing, for example.

Simile sees his sessions with Graham as providing both educational benefits and acting as a source of encouragement, “It’s not meant to have some sort of, like, overarching, gigantic outcome. It’s more about like, what’s this kid interested in, and how can I support him in reaching these goals and in doing these creative projects that he likes to do?”

For the past couple of years Graham and Simile have been collaborating on constructing video game soundtracks. When coming up with melodies on the piano or on GarageBand, Simile asks Graham to try and articulate how certain sounds make him feel. The score that captured Graham’s attention that week was Puppet Master’s theme song. “The drums sound like they are rolling up to your doorway,” Graham said with excitement.

When describing the sounds he wanted for his own video game, Graham used adjectives like “simple” and “summer” as well as more technical terms like “arpeggio.” After some trial and error, Simile came up with a three-note melody on the piano that Graham said he liked. “Can you say what you like about it?” Michael asked. “I don’t know,” Graham said, “I just like it.”

Dan, Graham’s father, offered this, “I think the way Emily [Graham’s mother] and I view a lot of this is with the kids that we have and their unique needs [this] is kind of building the village around the boys for safe spaces where they know they can go and talk to someone. And building that relationship with Michael is really important, and we’ve seen it as Graham has come from kindergarten to seventh grade because, you know, there’s certain things that, as a kid, you don’t want to talk to your mom and dad about, right? But Michael is a safe space, and one of our big goals is giving the boys an outlet in those situations to express themselves.”

Dr. Laurel Young, professor of music therapy at Concordia University in Montreal, cautions that “Music is not an inexpensive ‘one-size-fits-all’ miracle cure. (That sounds suspiciously like snake oil to me and current research cannot support this claim.) However, it is a powerful creative medium that, when used with skill, sensitivity, knowledge, and personal insight, has the capacity to address the diverse complexities of the human condition in unique and transformative ways.”

When music therapists take care to personalize the music to the individual, it can be very effective, Ammon says. But, just like any form of therapy, the arts have their limits.

“I would say at the end of the day again, if [music] is not something that a person enjoys or that speaks to them, then you’re at a catch-22, you’re at an impasse. So it all comes down to building that relationship and getting to know the person. And sometimes that happens quickly and sometimes it doesn’t,” Ammon stated.

Music therapy in the home of Rock & Roll: Building community through music

Northeast Ohio has long been a center of music therapy. The Music Settlement was among the first in the country to offer a structured music therapy program. In 2023, Ohio became one of only 10 states to offer certification at the time. Ed Gallagher, the founder of the Creative Arts Therapies Program at Beck Center, co-chaired the Ohio Music Therapy Task Force, which advocated for 15 years for music therapy licensure in Ohio.

Gallagher argues that the profile of music therapy in the region has been growing. “Earlier in my career we would have to explain what we are whenever we entered a room. Now it feels like we are already part of the conversation.”

Beck Center’s program itself has grown from a music therapy-focused service to one offering “adaptive” classes in music, art, dance and theater, tailored to individuals that might require accommodation beyond what you’d find in a traditional lesson. Ammon says students of all abilities are welcome and that many of the clients they work with have developmental disabilities. The arts therapy specialists in the program, according to Ammon, are uniquely qualified to work with those individuals.

Nikki, for example, before she started her music therapy sessions with Gavin, participated in an adaptive dance and movement class, where one of the activities involved dancing with colored silks. While recreational, the class also worked towards a more general goal of improving her gross motor skills.

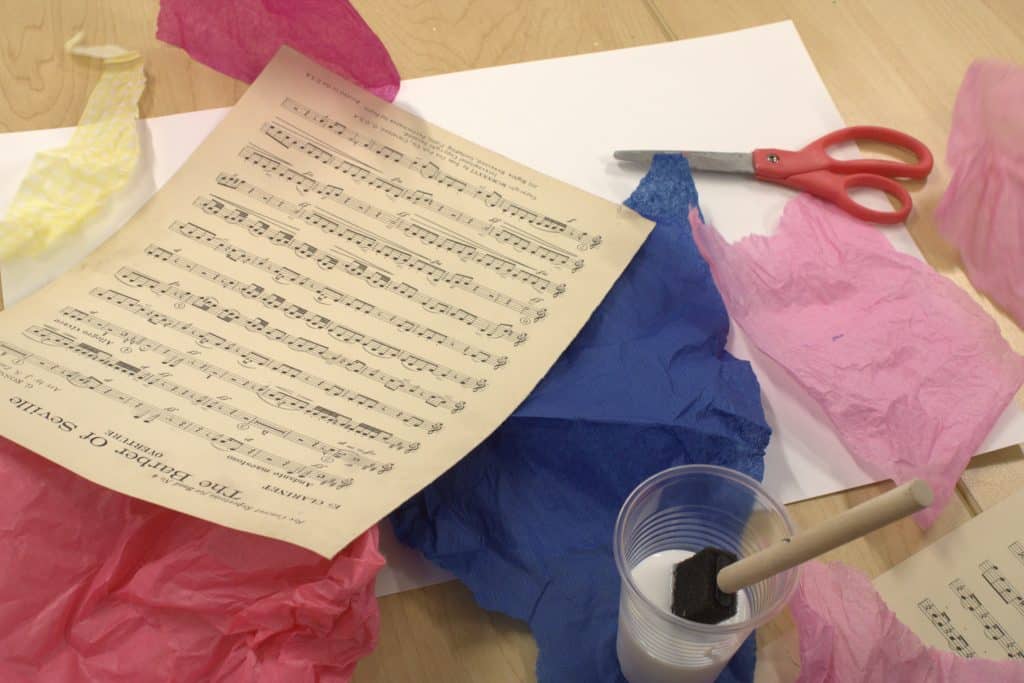

I observed the Adaptive Art Maker’s class for adults, taught by Jocelynn Mejstrik, adaptive art specialist. Jocelynn has been teaching adaptive “art as therapy” classes at Beck for four years and will start as the first full-time art therapist at Beck Center next year. She completed her Master’s in counseling and art therapy this past May at Ursuline College and is preparing for her board exam.

“Art therapy is not about the product, it’s about the process,” Jocelynn says. “As long as you’re feeling something while you’re doing the art, that’s all that matters. Everyone thinks they have to be good at art to do art, and that’s not the case, like you come and create something, and it’s all about the experience and what you’re going through while you’re creating the piece. And for these individuals, I think it gives them a feeling of independence. They’re doing something on their own, and something that they’re proud of. I just want people to understand that, just because people are categorized as special needs doesn’t mean that they can’t do the same things as other people,” she added.

While less goal-driven than traditional arts therapy sessions, the adaptive arts classes are still therapeutic in nature. They focus on the recreational experience of being creative while supporting the social aspect of clients’ well-being, according to Ammon.

The therapists I spoke to at Beck Center share a sense that the program doesn’t just provide arts therapy. It uses creative arts therapy to create community and belonging in Lakewood and beyond.

“Beck Center specifically is a really community-focused place. Not only do people from all over come here, but we also go out [to the community]. So that’s one of the things that I think separates Beck Center,” Simile said.

According to Ammon, Beck Center contracts out music therapy as well as adapted art, theater and music to all of the special education programs in the Lakewood City School District. They provide early childhood music to all of the preschools in the Lakewood City Schools and at a number of other facilities in Lakewood. Gallagher says they’ve been providing these services for approximately 10 years. But Lakewood isn’t the only neighborhood where they’re active.

“We do a lot of programming in Cleveland, in the Cleveland area, we do everything from Rocky River. We go out to Strongsville. We’re in Highland Heights and Independence. We even are out in Orange and Beachwood. Euclid, you know? We go all over,” Ammon said.

“What I would hope for people to glean from anything about our programming is just that Beck Center is a place for everyone,” Ammon says. “We are committed to making it a place of belonging, and that everyone does have a place here. I always tell people that the reason that I love Beck Center is because it represents the kind of world that I want to live in, and that, more than ever, now holds true.”

The Creative Arts Therapies Program now includes a combined 11 part-time and full-time employees across several specialty areas. Music therapy continues to be the largest specialty, with three full-time, licensed and board-certified music therapists on the payroll. The other spots are filled by part-time arts, theater, dance and early childhood music specialists.

Gallagher credits Ammon with overseeing much of the program’s growth. She says a lot has changed over time, not just the class and therapy offerings, but the number of people they’ve served and the number of locations they’ve served.

“Our hope and our goal is to continuously expand. I, of course, would love to have a full-time staff member for each art form at some point in time. The closest to that, is we are looking at expanding art therapy …I’m really excited to see what the future holds for all that,” Ammon said.

More information on the Creative Art Therapies program can be found at www.beckcenter.org/education/creative-arts-therapies.

Beck Center for the Arts accepts family services funding for creative arts therapies programs through the Cuyahoga County Board of Developmental Disabilities and Greater Cleveland’s Positive Education Program. Financial assistance is also available to those who qualify. For more information on how Creative Arts Therapies can complement a therapeutic regimen for you or a loved one, please contact: Tracy Ammon, MT-BC at

tammon@beckcenter.org.

Creative Arts Therapies’ services are available to community-based agencies, schools, early childhood centers, adult activity centers, and health care facilities throughout Northeast Ohio. Services may include art therapy, music therapy, and adapted programs in dance and theater. Facilities interested in contracting Beck Center services can reach out to Kelsey Heichel, associate director of community engagement, at kheichel@beckcenter.org

We're celebrating four years of amplifying resident voices from Cleveland's neighborhoods. Will you make a donation to keep our local journalism going?