On a Thursday afternoon in June, downtown Superior Avenue looked markedly different. It had been transformed into Metropolis: a fake city where fictional heroes fight fictional villains. Meanwhile, inside the Cleveland Public Library, dozens gathered to hear about a real and relevant civic issue. One with muddier morals and no real hero to root for: providing public funds to sports stadiums.

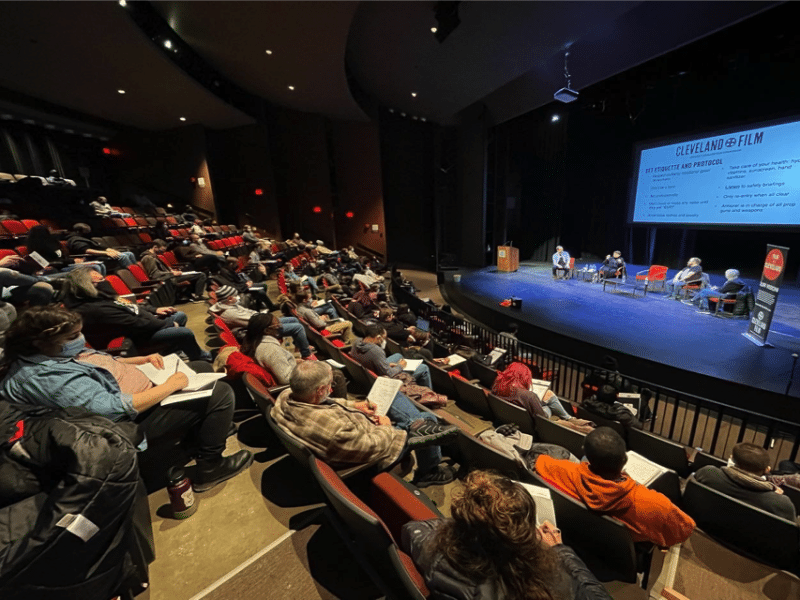

A panel discussion hosted by Cleveland City Councilman Brian Kazy brought a spectrum of experts who argued that building a new Browns stadium with Cleveland tax dollars would not bring significant economic benefits to the city.

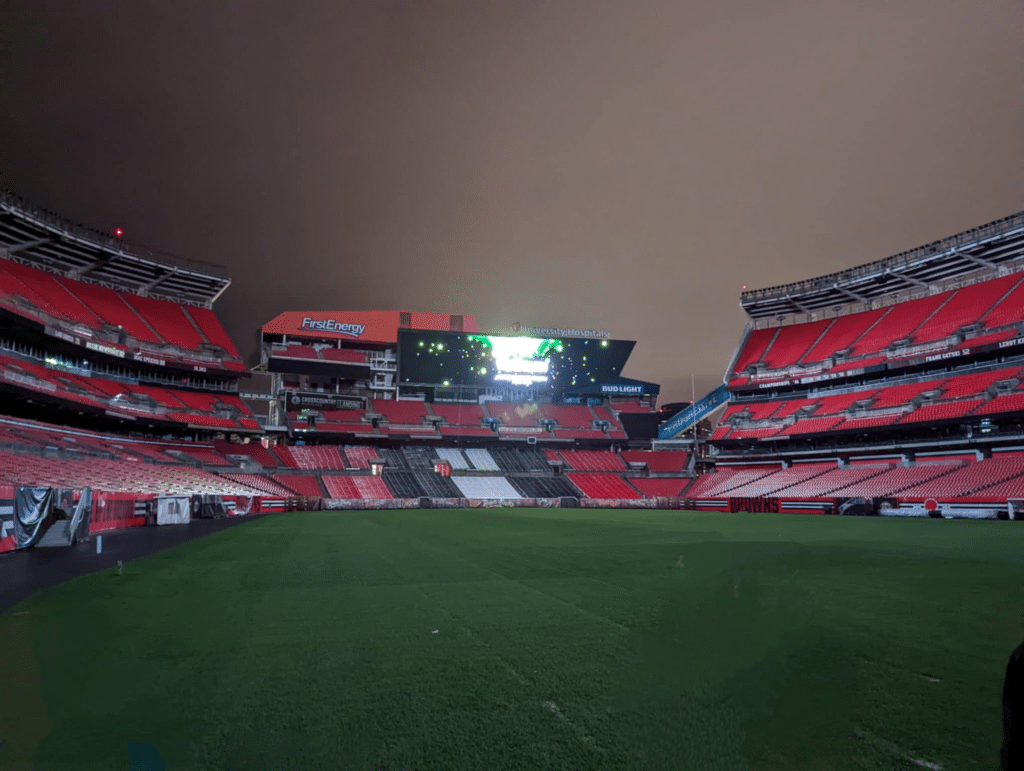

Jimmy Haslam, who has a net worth of about $8 billion, according to Forbes, is looking for Cleveland taxpayers – with a median income of around $25,000 – to split the bill on a $1-$2.5 billion stadium renovation. The proposal includes a range of options including a $1 billion stadium renovation or the construction of a new domed stadium for upwards of $2.5 billion.

At an average Browns game, only 15% of attendees live in the City of Cleveland. In fact, the vast majority of game attendees don’t even live in Cuyahoga County, according to reporting from Cleveland Scene. Panelist Ken Sillman suggested that most Browns fans are interested in a team that competes for the playoffs – not in a luxury stadium – and the financing of a new stadium should reflect that.

“Season tickets annually sell out, and there’s an 8,000-person waiting list for season tickets. What about the fans in the expensive seats, who are probably mostly from outside the county, and, I suspect, are really the driving force for the Haslams’ requested $1 billion rebuild? I’m submitting that they, and not city taxpayers, ought to pay for the luxury upgrades of the stadium either via higher ticket prices, which would allow the owners to recoup an upfront outlay, or via personal seat licenses,” Sillman said.

The Haslams and other sports team owners cite great economic opportunity as a justification for the public subsidies. In a statement released by the Browns owner in March, Dee Haslam did just that.

“It could be transformative for the community. I mean, obviously there’d be a lot of jobs regardless of whether we remodel or new construction, but just the economic development piece is big for both. It’s just a huge opportunity to set a vision for Cleveland and what we could be. I think it’s an exciting process for us and the community,” she said.

But the evidence is stacked against the Haslams’ claim that the project could be transformative, the panelists argued.

“There is zero evidence in 30 years of peer-reviewed academic research that a professional sports team in a city generates any substantial new jobs, raises wages, raises income, raises property taxes – there’s just no evidence of that. What professional sports teams are good at is moving economic activity around to different parts of a city. So if a new NFL stadium is built out by the airport, it’s going to move a lot of economic activity that would have taken place downtown or somewhere else in Cleveland and concentrate it there, and that’s completely consistent with 30 years of research,” said panelist Victor Matheson, a sports economist and author.

Evidence is also mounting that, given the choice, taxpayers may not want to shoulder the burden of sports stadium upgrades – voters recently shot down stadium taxes in Kansas City and the Phoenix suburb of Tempe last year. More often, the decision is not up to the residents. Instead, elected officials and city administrators negotiate and make the call to allocate taxpayer dollars to these multi-million or billion dollar projects at the request of billionaires themselves.

“The one place we know there is a gigantic economic impact associated with building a new stadium: franchise valuation. You build a new stadium and the franchise owner becomes wildly more wealthy. The more money you give as part of the project, obviously the less money out of the owner’s pocket,” Matheson said.

We're celebrating four years of amplifying resident voices from Cleveland's neighborhoods. Will you make a donation to keep our local journalism going?