Nearly three years after Cleveland leaders launched a master plan for redeveloping the Clark-Fulton neighborhood with professional and residential input, one of its cornerstone housing developments is moving forward. The Arch at Saint Michael project will repurpose classrooms and offices into 46 new low-income multifamily apartment units for seniors in the Saint Michael Archangel Roman Catholic Church’s former school and convent.

Six times during the day, Clark-Fulton residents learn whether it’s 6 a.m., noon or 6 p.m. as several thousand pounds of brass spring to life in an open-aired chamber amid the 233-foot steeple at Saint Michael Archangel Roman Catholic Church. Before the end of 2025, those bells will sing their rapport to 46 new sets of ears after CHN Housing Partners and Johnson G. Johnson (JGJ) Construction crews finish their $23 million redevelopment of the church’s 117-year-old former school and convent building.

The building sits at the corner of Scranton Road and the avenue from which the neighborhood derives the “Clark” of its name. However, St. Michael’s church has not had its name on the deed of the three-story building at 3146 Scranton Rd. since it sold the ex-school in 2004. Having been used as church offices until the county purchased it in 2017 and then sitting vacant since then, the building will need at least 17 months of work before it’s deemed safe for senior citizens and opened under the name “The Arch at Saint Michael” sometime in 2025.

“We’ll make some landscaping improvements, that’s part of the plan,” said Jennifer Koperdak, the CHN Senior Project Manager who will be overseeing the construction projects once crews begin their work in 2024.

“There is going to be a space between the school and the convent for residents to hang out with each other,” Koperdak added. “We’re going to repave the parking lot because it absolutely needs it. We’re going to have new fencing, fix the building structurally and make sure it’s safe.”

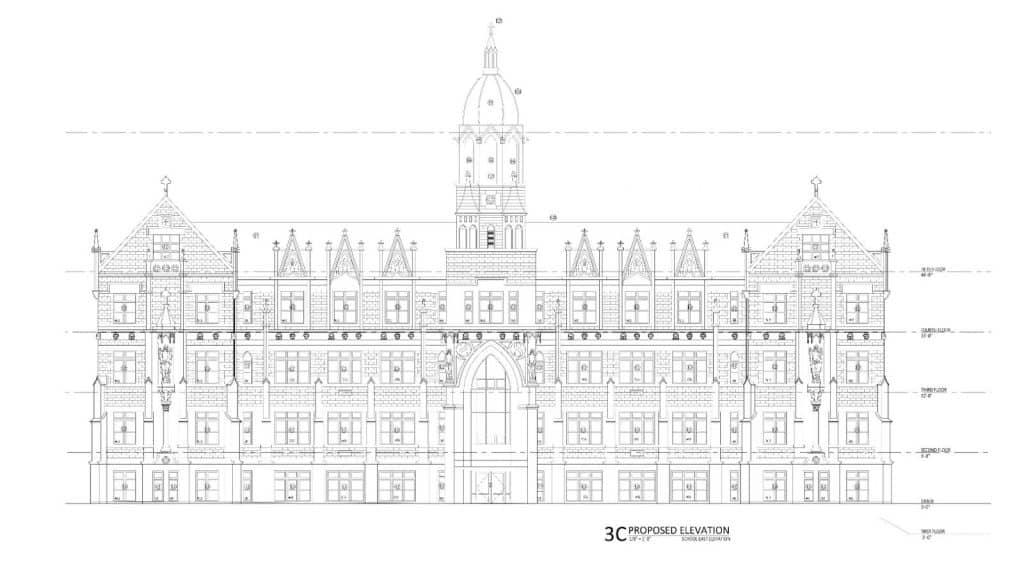

Based on the designs of architect Adolphus Druiding, a German immigrant who eventually landed in Chicago, and completed in 1907, the building is now owned by the Cuyahoga County Land Reutilization Corporation (also called the Cuyahoga Land Bank), which is leasing it to CHN. The school building, of nearly 81,000 square feet, and the smaller convent structure behind it will serve seniors with annual incomes ranging from $30,132 to $48,600.

That translates to between 31% and 50% of the near-west side’s local median income, a stipulation added due to the project’s use of low-income tax credits in construction. Historic preservation credits also play a role, helping the building retain its Gothic Revival character while footing part of the bill.

Such credits will also increase the workload; CHN Vice President of Construction Robin Holmes said the adaptive reuse project will involve demolishing and gutting the structure’s interior until only its rocky bones remain. The existing water, electric, central air conditioning and heating systems will be replaced in their entirety before crews set to work subdividing old classrooms into new units with bedrooms, living rooms, bathrooms and kitchenettes that will serve as solid senior housing, a dwindling resource in Cleveland.

“The seniors, they either end up moving in with family members (or go to assisted living homes because) there’s such a huge need,” said Ward 14 Councilwoman Jasmin Santana, who oversees Clark-Fulton as well as portions of the Stockyards, Tremont and Brooklyn Centre neighborhoods. “There’s nowhere for them to go. What we’re doing is spending money on home repairs for (them).”

Both the historic and income assistance credits both provide tax abatement necessary to get the project off the ground, making them welcome tools for Santana. First elected to City Council in 2017, Santana knows the majority of her constituents are among Clark-Fulton’s roughly 11,000 residents and has put an emphasis on development to keep neighbors around. That population count has hovered within the same range since the 2000s following a steady decrease after it peaked at over 21,000 residents in the early 1940s.

The arrival of highways and westbound white flight halved Clark-Fulton’s population and uprooted thousands of homes in the intervening decades. Puerto Rican and Latino immigrants who had emigrated to Northeast Ohio to operate Lorain steel mills began replacing some former occupants starting in the 1960s, but the neighborhood is plagued by vacancies.

Santana said over 400 unoccupied homes and empty lots serve as trash bins collecting parked cars and shopping bags in the area bracketed by Train Avenue to the north and the upward curve of Interstate 71 to the south.

The Arch at Saint Michael, then, is intended to simultaneously address the overall lack of affordable housing in (and around) Cleveland, but also the loss of its Latino and aging populations within the agenda of the Clark-Fulton Together Master Plan.

Part of the plan

The Arch at Saint Michael forms the final leg in a tripod of income-adjusted housing projects alongside Northern Ohio Blanket Mills. Before 2025 ends, Koperdak said the Arch will start leasing its 60 apartments for those earning 60% or less of area median income after entering rental agreements with commercial tenants at its location east of the Clark Avenue and Fulton Road intersection.

The third piece is Via Sana, where Santana said 70 townhome-style apartments are now fully occupied at 30-80% of the annual median income. MetroHealth is managing the property and will operate its future Opportunity Center at the Via Sana building, located on the northeast corner of the hospital system’s main campus where Scranton Road meets West 25th Street.

It all constitutes extensive development in a neighborhood that Santana, who grew up on the West Side to become Cleveland’s first Latina council member, said is in need of housing for younger and older residents.

“When I was first elected I met with (Cleveland’s former mayor) Frank Jackson,” Santana said. “He knew of no investment, and since I’ve been here there has been no investment in Ward 14, especially around Clark-Fulton. Not from the city.”

Aside from the shared intent to help shield Clark-Fulton from rising rents, the projects are also linked together based on their selection to each receive $1 million in state-supplied FHACT50 Building Opportunity Fund credits. The Ohio Housing Finance Agency (OHFA) distributed the credits for use in one “mixed-income” neighborhood in each of the state’s three largest cities in 2021 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Fair Housing Act.

The renovation work is also happening within eyeshot of the new CentroVilla25 mixed-use vendor market, whose $12 million price tag also benefited from the $1 billion investment MetroHealth announced to improve the pockmarked streets and create a public park bracketing its main branch emergency room, pharmacy and specialty services pavilion.

Building the Arch

Its proximity to the hospital campus notwithstanding, Santana said the project was a no-brainer when she applied to FHACT50 due to the building’s size and position. “Think about Scranton. It’s walkable and can be a source of transportation. And, of course, you have to find a building that’s big enough and has potential. St. Michael’s was easy to pick.”

Aside from the $1 million from FHACT50, CHN’s Jennifer Koperdak said Cuyahoga County contributed $450,000 to help with the project. More than half of the $23 million came from the OHFA’s 9% Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) Program that can cover up to 70 percent of total project costs as well as the Ohio Historic Preservation Tax Credit Program.

Federally, the Department of Housing and Urban Development kicked in $3.5 million through a program promoting the repair of structures for senior housing and will continue contributing via its Project Rental Assistance Contract.

In March, Cleveland City Council voted to supply the project with nearly $3 million between the city’s HOME-ARP grants (which leveraged money invested via the American Rescue Plan Act to help compensate housing projects) and the city’s community development block) grant.

“This is probably going to be the most complicated building that I’ve worked on… because of the structural integrity issues we have,” said Holmes, who brings 30 years of experience on government and civilian development to her role overseeing construction for CHN.

Even before JGJ Construction can enter the building to begin reorienting posts and beams and shaping fresh plaster into new rooms, CHN hired the architectural services of HDMS & Standard GIS Inc. out of Little Rock, Arkansas to draw new building diagrams.

Holmes said the county was unable to provide documents, like architectural drawings, that would have served as bases of comparison when determining what work was needed to fit within historic credit guidelines alongside the California-based HP (historic preservation) consultants. There was a large cross affixed to the building at one point, for example, but that has been lost to time.

Brick and more than meets the eye

As one drives along Scranton Road as the street heads north into Downtown, the Arch is the only building to bear a stone edifice for the hundreds of drivers traversing the road for MetroHealth purposes.

When German and Eastern European immigrants first settled the area, Berea sandstone served as the common pick for large-scale builds; now, lined with aging homes and steel-beam new builds around the hospital campus, Clark-Fulton’s face has changed. As such, Koperdak, Holmes and Santana are prioritizing preservation of the building’s original character as part of its refresh.

“We can’t change the look of the building, we have to keep its historic integrity intact,” Koperdak said. “We can’t paint the building, can’t remove masonry or add our own type of siding. Everything has to stay historically accurate, on the inside of the building, too.”

Between $3.5 and $4.6 million of the project’s total $23 million cost will be used to renovate the building’s exterior. “That’s very atypical,” Holmes said as she gestured at leaning gables and windows set deep into the stone, both of which will need serious attention.

While CHN’s VP of construction is unsure of what material will be used for the windows, she said crews will spend a decent amount of time re-mortaring the structure’s stone buttresses and other critical supports by charting the location of each 20-plus-pound stone and then gluing them back together.

“We’ve got structural reviews and those (stones) need to be taken down and put back together like a puzzle after we reinforce the structure,” she added. “All the structure has to be put back.”

Residents of Clark-Fulton and beyond will have a lot of rubbernecking to do when passing the fenced construction zone over the next few months; hundreds of tons of stone will be lowered onto the asphalt lot between Prame and Althens avenues. The parking area will eventually see new tar, windows will take a more form-fitting approach and trucks will come and go for over a dozen months as an old structure is made to retain its historic dress while being revitalized inside.

“Mixing new and old makes everything, one, more aesthetically pleasing and, two, (helps) tell a story,” Koperdak stated. “This is my personal point of view: These historic buildings tell a story of the sort of nostalgia we can carry with us into the future…. They help tell the story of what was once here and remind us of this great architecture, this great beauty and the gems that are in these neighborhoods. Buildings aren’t designed and don’t look the way they used to 100 years ago.”

Other senior–centered projects under CHN’s belt include the Hough Heritage building on East 97th Street; Willoughby’s K&D group is also renting low-cost properties to seniors throughout Cleveland, Akron and Canton. Catholic Charities, Diocese of Cleveland offers subsidized assistance for St. Augustine Health Ministries’ Emerald Village senior living community in North Olmsted. Over on the West Side, Cuyahoga County land bank parcels will eventually qualify for Ohio’s LIHTC tax credits program after the 52-unit Walton Senior Apartments won state support over proposals like Salus Development’s “Detroit Avenue Senior Housing.” After55 offers a registry of the area’s affordable housing available for older adults.

Keep our local journalism accessible to all

Reader support is crucial as we continue to shed light on underreported neighborhoods in Cleveland. Will you become a monthly member to help us continue to produce news by, for, and with the community?

P.S. Did you like this story? Take our reader survey!