This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project – Cleveland, a nonprofit news team covering Ohio’s criminal justice systems. Sign up for their Cleveland newsletter and Facebook Group, and follow The Marshall Project on Instagram, Reddit and YouTube.

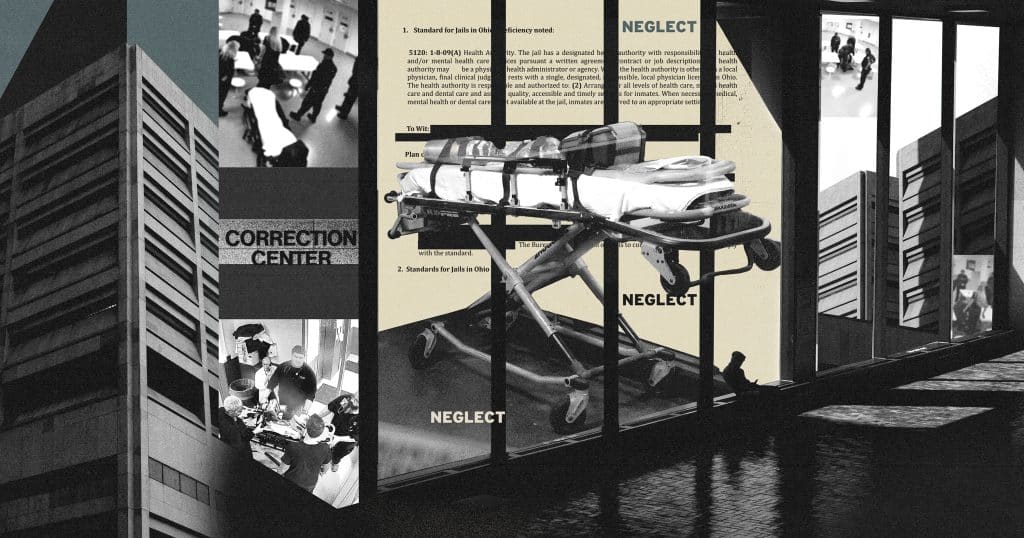

Michael Papp’s body was cold and stiff inside his secluded Cuyahoga County jail cell when a corrections officer finally opened the door.

Officers reportedly walked the pod 50 times, peeking inside cells for signs of life. Yet, somehow, they missed a dead body.

The officer went on to check 19 other cells before sitting down at a phone to call for help. A responding nurse took one look at the body and walked away in apparent frustration.

Jail administrators and staff had once again failed to learn from past mistakes.

Medical neglect, poor monitoring and botched intake screenings have contributed to at least half the jail’s 20 deaths since 2020, according to a Marshall Project – Cleveland analysis.

In a 2025 compliance review of Papp’s case, state investigators called the staff response unacceptable and disgusting. It was evident, one inspector wrote in her scathing notes, that jail leadership hadn’t prepared staff for life-threatening emergencies, as directed in the state’s most recent investigation.

While investigators probed Papp’s death, another man died in custody after not receiving adequate care, according to a compliance review.

The string of largely preventable deaths — mostly attributed to natural causes or drug overdoses — lay bare how Ohio’s weak system of jail accountability has failed to protect those held behind bars.

“It’s just a symptomatic problem of a complete breakdown of what was going on [in the jail],” said Jeff Crossman, a local attorney and former state lawmaker. “One death, you could say, ‘Well, that’s a terrible tragedy, an unfortunate incident, a one-off.’ You start having repeated deaths. I mean, that really is alarming.”

County officials have denied The Marshall Project – Cleveland a tour of the jail or an interview with Sheriff Harold Pretel, who oversees the operation.

A county spokesperson said staff attorneys advised against commenting on in-custody deaths.

“That said, the safety of staff and residents at the [jail] remains our highest priority,” Kelly Woodard, director of communications for Cuyahoga County Executive Chris Ronayne, wrote in an email to The Marshall Project – Cleveland.

Woodard noted that the county has added more drug-sniffing dogs and increased staffing to improve intake monitoring. Woodard did not say when or how many officers were added.

A ‘relatively useless system’

States set and ensure compliance with standards for local jails. In Ohio, jail administrators must report deaths to the state Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, where inspectors with the Bureau of Adult Detention review each case to determine if any standards were violated.

“Ultimately, it is the jail’s responsibility to ensure compliance with the standards,” JoEllen Smith, communications chief for the Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, wrote in an email.

The Marshall Project – Cleveland’s analysis found at least one failed standard in more than half of all Ohio jail deaths in 2023 and 2024.

The state reviews include improvement plans created in coordination with local jail officials. But those plans are not always followed, and state officials have not flexed their authority to push jails into compliance.

Ohio law allows the state prisons director to sue sheriffs into compliance with state standards. But Gov. Mike DeWine, in response to a 2024 USA Today investigation of 220 recent Ohio jail deaths, called legal action a nuclear option.

And the state’s Bureau of Adult Detention can’t slap a closed-for-business sign on a failing jail like county health inspectors can on a troubled restaurant.

“If all they can do is oversight and there’s no teeth and they can’t close the jail, then it’s [a] pretty, relatively useless system,” said Marc Stern, a correctional health care expert and former head medical officer for Washington’s state prison system.

Fatal flaws

Twenty hours before his death in July 2024, Papp, 38, told Cuyahoga County jail staff when booked that he had recently used fentanyl and often suffered from severe withdrawal.

A drug-sniffing dog was not present when staff searched Papp and failed to find narcotics concealed in his rectum. A jail camera captured him freely using an unknown substance. Toxicology testing detected fentanyl, methamphetamine, cocaine and other chemicals in his system.

Officers isolated Papp in a psychiatric seclusion cell instead of closely monitoring his health. There’s no evidence that medical staff checked him. While alone and locked inside his cell, he did not touch three meals.

Papp’s death touched on categorical failures found in several other deaths in recent years.

Poor monitoring is a longstanding problem, according to state investigators, especially in pods designated as red zones due to low staffing.

- In 2020, state inspectors wrote that cell checks were made in “a rapid manner not allowing sufficient time to observe the status of inmates” when Devauntae “Lea” Daye was found dead of an accidental overdose in his overcrowded cell.

- In 2022, corrections officers took more than the state minimum of one hour to check on Adam Weakley, Melissa Musson and Mark Turner Jr. — each found unresponsive in their cells.

- In 2023, Nathan Myers was returned to the jail after being treated for an overdose but not closely monitored. He died of a second overdose within the week.

State inspectors also found that the jail was not screening anyone for opiate withdrawal when Musson and Turner died on the same day.

The jail failed to provide adequate medical care or respond in a timely manner to complaints and emergencies, state inspectors found.

- Edrick Brooks died of high blood pressure and heart disease in 2022 while left unattended in the jail’s sally port.

- Glen Williams Jr.’s multiple requests for medical attention went unanswered in the days before he died of a ruptured aorta in January 2024.

- Nathan Kinney did not receive appropriate medical care before he had a heart attack in the jail’s gym in March 2025.

“He was there for three months and never seen by anyone,” said Kinney’s cousin, LaDawna Hill.

Still ‘shocked and appalled’

After a 2018 U.S. Marshal’s report detailed inhumane conditions, a coalition of community advocacy groups demanded that the jail comply with state standards, including proper medical care and opiate withdrawal screening.

That year, the state cited the Cuyahoga County jail with 84 violations after finding few issues in previous inspections. For the first time in Ohio history, Dewine ordered monthly inspections until state inspectors noted significant progress and improvement by October 2020.

DeWine increased the number of state inspectors from three to nine, adding a registered nurse to the team and passing a rule that allows for surprise inspections. Findings of failed standards would now be shared with county prosecutors and local judges.

But Ohio’s system of accountability, built on encouraging rather than forcing sheriffs to act, was left largely intact.

In 2020, Crossman and state Sen. Nickie Antonio, a Lakewood Democrat, pitched legislation to allow state officials to shutter failing local jails. Their action was spurred by several local headlines about avoidable deaths and poor conditions in the Cuyahoga County jail.

“We were shocked and appalled that anybody would die in the custody of Cuyahoga County, and that there had to be some improvements,” Antonio said.

Antonio introduced another bill that year that would have established standards for opiate withdrawal screening and care in Ohio jails. Such withdrawal can be fatal if not medicated.

The bill was dubbed Sean’s Law after Sean Levert, son of famed O’Jays lead singer Eddie Levert, died in the Cuyahoga County jail after being denied prescription medication in 2008.

The bills, however, died in committee.

Jada Johnson, a pregnant woman who spent six days in the jail’s medical pod in January 2025, said she wasn’t surprised by the neglect and lack of accountability.

Johnson said she slept on the concrete floor of a cold cell, worried about falling off her bunk bed. She didn’t receive her epilepsy meds the first two days of her stay, she said.

In her pod, she said she watched a woman’s finger change color before getting treatment for an infection, a diabetic woman demand insulin and a woman with a history of ectopic pregnancy emerge from her cell with a blood-soaked menstrual pad.

Nurses were 30 feet down the hallway but seldom responded quickly, if at all, to complaints, she added.

“They take their time with serious things,” Johnson said.

Keep our local journalism accessible to all

Reader support is crucial as we continue to shed light on underreported neighborhoods in Cleveland. Will you become a monthly member to help us continue to produce news by, for, and with the community?

P.S. Did you like this story? Take our reader survey!

![Cleveland activist organizations call for general strike at anti-ICE protest [photos]](https://d41ow8dj78e0j.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/28094754/IMG_8580-800x600.jpg)