It’s sometimes cheaper and easier to buy a new copy of a book than to repair an old one.

But the new one wouldn’t be the same.

“People want their book,” says Ellen Strong of Strong Bindery, which is tucked inside Loganberry Books, 13015 Larchmere Blvd. “They’ve put themselves into their book.”

It may have been held in their laps, pored over, highlighted or dozed over. It may have marginalia, clippings, a family tree, an author’s autograph or a loved one’s inscription.

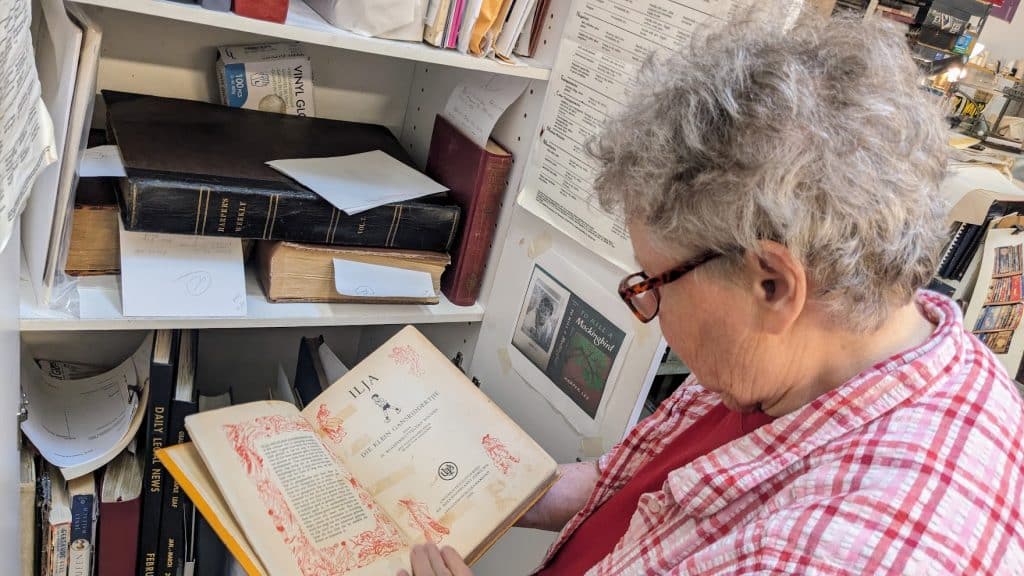

For about 55 of her 80 years, Ellen Strong has been practicing the increasingly rare craft of rebinding and repairing books, magazines, diaries, posters and other paper goods. She also makes journals, notebooks, labels, boxes, sleeves, and lapel pins in the shape of books.

Her favorite expression is, “Every book is different.” She has worked with covers about as small as a square inch and as big as 6 square feet. She has repaired a book from 1537 and made new books by binding manuscripts. She has charged anywhere from $10 to $10,000, though usually between $50 and $250.

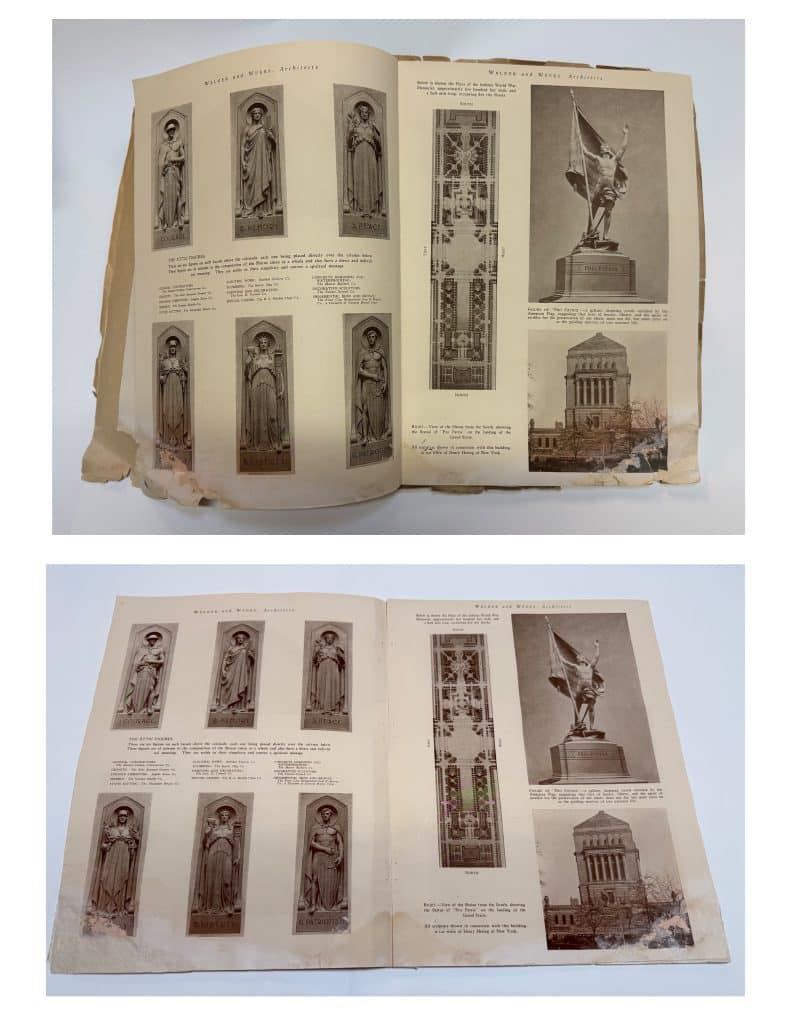

Her shop spent much of the summer repairing a 1930 Architectural Review of the Mississippi Basin devoted entirely to Walker & Weeks, the Cleveland architects of Cleveland Main Library, Public Auditorium and other local landmarks.

Kelly Pontoni, one of the bindery’s two regular employees, along with two part-time workers, spent four to five hours per page on the journal’s 110 pages. She bathed and pressed each page twice. She soaked bits of similar fiber, mashed them together, and attached one bit at a time to the badly worn corner.

Her work on the journal was funded by a Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Grant Award of about $2,937 from the Ohio Arts Council.

Strong was born Ellen Strong Hauserman and dropped the surname for business. Her brother, Martin Hauserman, is another expert in old texts, having spent 35 years as Cleveland’s city archivist.

Strong has lived all her life in Cleveland Heights except for a few years at Marquette University and in New York City. In childhood, she loved bedtime stories. At college, she peeked at pocket books during dull lectures. She collects mysteries and also likes books from the 16th through 18th centuries.

She worked at Cleveland’s Publix Books and started restoring books there. She co-founded Coventry Books in 1972, bought out her partners, closed the store in 1985 and started binding books for other sellers, for librarians and for individual owners.

For 20 years, Strong Bindery was at the Murray Hill Galleries. Then the shop moved inside Loganberry, a popular, eclectic venue for new and old books. Strong has crammed a side room with presses, shears, stamping machines, weights, bone folders, other tools, paper, leather and, of course, books.

Why do books go bad? Blame bookworms, dust, mold, mildew, spills, acid in paper, extreme temperature, extreme humidity, and too much love. Strong recommends storing books with as much exposure to air as possible, not pressing them against the back of the shelf.

Also blame bad repairs with harmful tape, glue or rubber cement. Strong says that several online videos give good tips for repairs. But most say nothing about the paper’s grain. She says to line it up the same way on every page, which usually means vertically.

Print was supposed to be marginalized by radio, television and the internet. Yet U.S. publishers sold 783 million printed copies of books last year, far more than the 648 million of 20 years earlier.

“Books are always going to be around,” says Strong. “Here at Loganberry, kids are getting stacks of books. It’s almost like it skipped a generation.”

The bindery and the bookstore are tenants of Brenda Logan, whose daughter, Harriett, runs Loganberry and hires Strong for tough repair jobs. The bookseller says, “Ellie is a careful bookbinder who understands the archival goal of keeping a book alive for the next generation.”

Satisfied customers include former Pittsburgh Mayor Thomas Murphy. “What a great job you did on the latest stamp album!” he messaged her this month. “I thought that it was beyond repair.”

For local customer Ron Kisner, Strong has put leather bindings on new books and repaired a tattered Bible given him by his parents for Christmas in 1955. Kisner says, “When you walk into her space, it’s like you’re going back in time. It’s almost like a curiosity shop. It’s so hard to find people with the skill she has. Milliners, hatmakers, bootmakers are all gone. She’s working away, doing amazing things. These books are coming to life again.”

Not surprisingly, Strong often finds herself reading on the job. “Sometimes it’s useful,” she says. “You have a sense of what the language sounds like, and you can adapt the binding to the kind of book it is.” She might, for instance, put a flowery binding on a flowery one or a sober binding on a scientific one.

How long will she keep binding? “I expect to die with a bone folder in my hand.”

Will the business outlive its childless owner? “I hope so. We have some ideas. But that’s another chapter.”

Pontoni and Strong will talk about the Walker & Weeks journal from 7 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. on Thursday, Aug. 28, at the monthly meeting of the Northern Ohio Bibliophilic Society at Loganberry Books, 13015 Larchmere Blvd., and on Zoom.

Keep our local journalism accessible to all

Reader support is crucial as we continue to shed light on underreported neighborhoods in Cleveland. Will you become a monthly member to help us continue to produce news by, for, and with the community?

P.S. Did you like this story? Take our reader survey!