Cleveland’s city government is revising its dual-department approach to addressing local cases of lead poisoning. The goal is to enact stricter testing measures to help better identify which owners still need to rid properties of the toxic metal.

Three years into Cleveland’s rollout of its citywide Lead Safe Certification initiative, Mayor Justin Bibb’s administration is working on a new model that would commit to more thorough lead removal procedures in the hopes of improving city processes.

The proposed change, though not yet fully defined by the city, follows an October report from the Cleveland Department of Public Health (CDPH) that revealed 11 children had tested positive for high lead levels after living in residences declared “lead-safe” on Cuyahoga County’s property lookup tool via the city’s Lead Safe Certification (LSC) process.

“My fear is the rest of the country has already moved on from this problem and it’s becoming uniquely Cleveland,” Cleveland Director of Public Health Dr. David Margolius explained. “Our rate is 2-3 times as bad as Detroit, 2-3 times as bad as Flint, Michigan ever was and twice as bad as Rochester, New York, was. So, all of these other cities we look to to find a way out, we’ve seen improvements over the same amount of time but we started with a much higher rate of poisoning.”

The goal of Bibb’s October 14 executive order is to add measures to the LSC process to reduce what the order labeled “the ineffectiveness” of Cleveland’s Lead Hazard Control program and the Lead Safe Certification (LSC) process that guides it.

Officials with the city’s public health and housing departments – the units respectively responsible for educating Cleveland citizens on lead and enforcing criminal law against landlords who fail to comply with testing – said the executive order suggests that the city is gearing up to require lead risk assessments.

The order’s language paints lead abatement as the more effective alternative to the city’s current model, which instead prioritizes lead clearance to protect children. While lead clearance tests determine if a residence is safe enough for humans to live in despite trace amounts of the toxic metal, assessments allow lead workers to highlight every shelf, nook and windowsill that needs to be cleaned and repainted to completely rid a property of lead.

The current certification process uses clearance exams before a residential unit is declared “lead safe” on Cuyahoga County’s property lookup tool, with such exams serving as final visual and chemical sweeps of a property. A lead risk assessment, meanwhile, takes an earlier and typically costlier approach.

Bibb, then, hopes stricter lead testing and clearance standards will help mitigate Cleveland’s lead levels and fill in the certification program’s cracks to prevent further missed cases. Currently, the report states, 11 percent of Cleveland children have extrememly elevated lead levels exceeding 5 micrograms per deciliter of blood. That makes children in Cleveland twice as likely to suffer from the most gastrointestinal, neuromuscular, nervous, hematologic or renal issues as a result of lead poisoning from living in homes with chipping paint or other lead sources versus anywhere else in the United States.

The goal is to reduce those levels to zero percent; Toledo and Detroit most closely trailed at roughly six percent in 2023. The numbers shift a bit when adjusted to account for 3.5 micrograms for deciliter, which has become the more widely accepted metric across the public health spectrum, per Margolius.

The tables, charts and maps among the nine-page public health report indicate that Cleveland witnessed a dropoff in childhood lead poisoning frequency from 53% to under 20% between 2005 and 2019, the year city council adopted the ordinance that lead to the creation of the LSC program and the Lead Safe Cleveland that helps manage program applicants. Since 2019, testing rates have continued to dwindle, though at a much slower rate, prompting the city’s recent decision to shift strategies.

Margolius attributes a slow certification program rollout (the ordinance did not require certification until March 2021; and the departments that administer the lead program are chronically short-staffed) and inconsistent data measuring for LSC’s ineffectiveness. He worries that adding a lead assessment exam may not be the sole solution to address the underlying departmental problems.

“We’ve been too hyperfocused on the number of Lead Safe Certificates produced and … not focused enough on how many properties we’re making lead-safe or lead-free,” Margolius added. “What we’re acknowledging with this data and the lack of progress is that, in order for that to change, we need more enforcement and more property owners to do risk assessments. We need even more safe and affordable units. We need more older homes that cannot be saved to be demolished.”

Testing the waters

An October press release announcing the city’s policy revision prioritizes data and lead risk assessments as the largest key changes coming to Cleveland’s lead abatement model, arriving on Nov. 26 in the form of an updated set of mandates for the Lead Safe certification process.

Further recommendations from the City of Cleveland Lead-Safe Advisory Board (LSAB), the same organization that issued 33 suggestions to create the LSC process back in 2019, will likely influence the new standards and how they will be enforced, according to former LSAB member Wyonette Cheairs.

Cheairs, who now handles some elements of the public-private Lead Safe Cleveland Coalition (LSCC) partnership via her role as program director at Enterprise Community Partners, said the city eventually decided to use 21 of those initial board recommendations when crafting its original certification legislation.

The LSAB most recently convened in late October and has another meeting on the books in early December to prepare a new set of suggestions to be used in defining and mandating the city’s approach to lead assessments, which will likely begin in 2025.

“How it’s being presented is that a lead-risk assessment is a higher standard in the sense (it identifies) more lead hazards where a lead clearance test does not,” Cheairs said in an interview. “The city is proposing a full-blown lead assessment is done first to identify the lead hazards and then a compliance schedule for the executive order to be put in place to bring the property up to clearing lead hazards. That’s where the higher standards come into play: in the end, to clear hazards following a lead risk assessment, you’re getting more into lead abatement as opposed to lead safe.”

To iron out assessment conditions, it will take further meetings between the advisory board, the LSCC, Cuyahoga County officials who administer the Lead Safe Program and other inter-departmental officials from the Mayor’s Office and Cleveland’s building and housing departments.

Cheair’s explanation frames the problem as a monetary issue, and Bibb’s order calls for an “accelerated” process to define it as one of timeliness and prevent further children from getting sick.

The lead up

In examining Cleveland’s lead metrics versus those of other Midwest cities where lead levels are also high, Margolius said the October lead report reveals a tough and historic problem. Developers have been adding to Cleveland’s housing stock since the city’s founding, and it’s going to take more than the three years of rollout and data-gathering to figure out what structures need remediated.

Over 90 percent of Cleveland’s standing homes first sold or rented to their initial tenants prior to the 1978 federal ban on lead paint, meaning interior walls would have received at least one coat of potentially toxic paint. The subsequent four decades saw the loss of population and the more recent influx in absentee landlords.

“Cleveland’s lead poisoning rate was so much worse than all of our peer cities, despite all of our efforts and the great people working on this,” Margolius explained.

While Cleveland’s citywide initiative is the most all-encompassing approach focusing on lead abatement in the city to date, the municipality’s efforts are far from the first to highlight the phenomenon in the region. Case Western Reserve University’s Center on Poverty and Community Development, where Dr. Robert Fischer serves as director, has been looking at childhood poisoning data using public health research from Cuyahoga County since 2000. Fischer identified a litany of reasons why Cleveland struggles more with reducing its lead levels versus other cities, putting the impetus on poverty as opposed to paint.

“You think about the age of our housing stock, that’s marker number one,” Fischer said. “We have a lot of aging properties.

“As we had population loss, specifically around 1950 out of the core of the city, that. . . turned a lot of former owner-occupied properties into rentals. We have a lot of owners in general who are in poverty. A third of our owners are (below median income). Just the ongoing maintenance cost of properties is hard to achieve if you’re struggling financially. For owners who (rent out and) don’t have that concern, it is a business decision to be made about whether to make improvements on these properties or not. If you look across the city, you see that neighborhoods with a high number of rentals are in consistent poverty, and that’s where we see the most hot zones of lead poisonings,” he said.

Fischer said programs like home visitation and birth outcome studies via the county’s Invest in Children partnership, which started in 2001, expanded the poverty center’s understanding of the problem. In 2010, Case Western entered into a data-use agreement to get testing results from the Ohio Department of Health. That data made it clear to researchers at the university that different household factors aligned with higher instances of childhood lead poisoning in various areas.

“We did a study over the first 20 years of life comparing lead-tested children to those (with lower levels) where the blood testing threshold was concerned,” Fischer explained. “It found (children with high lead levels) were showing up more frequently in every negative system from childcare development to lower academic performance, the juvenile justice system and lower earnings as young adults. It became evident that, if (lead is) left in its current state, civically we are paying a very high price downstream for these kids as they mature.”

Years after they can be prevented, those trickledown effects then manifest themselves to the social service organizations and city officials who interact with the particularly high lead levels that are distributed unevenly across the city at the ground level.

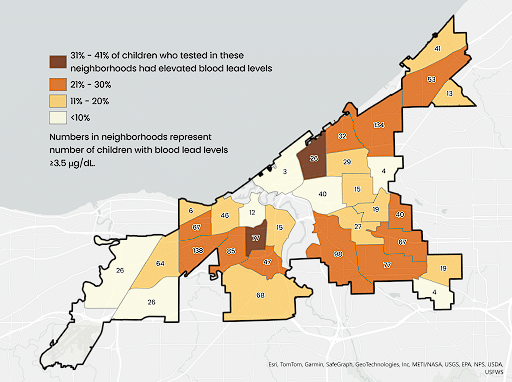

The recent city public health report showed that, in 2023, elevated bloodstream lead levels were more prominent in children living on the East Side than elsewhere. Tests focusing on any lead presence in the bloodstream (levels above 0.1 micrograms per deciliter), meanwhile, found that the West Side neighborhoods of Clark-Fulton, Cudell, West Boulevard and the Stockyards were more likely to exhibit childhood lead poisoning than their neighboring communities.

The let down

Around 2015, Councilwoman Jasmin Santana, who oversees Ward 14, which includes the Clark-Fulton neighborhood, said she identified lead poisoning as one of the negative factors impacting the primarily Spanish-speaking area. This became apparent when she toured the neighborhood to find out what social services were needed as part of her work with the now-defunct Hispanic Alliance.

“Most of these families didn’t speak English,” she explained in an interview. “Most of their properties were owned by out-of-state property owners. You’d run into – not only health issues – but building and housing issues: the house falling apart, the gutters, the structure of it, the poverty these families live in. I went into houses where kids didn’t … have beds or didn’t have any food. It was like a third-world country type of reality.”

While investigating Clark-Fulton, Santana discovered a network of compounding issues that cause or exacerbate lead presence throughout the city: landlords divorced from tenants by geography and language, citizens uneducated in leveraging their civil rights, a monolingual court system, homes with poor construction and kids reaching maturity in unsafe homes.

It’s a tangled mass of problems that no city department has the authority to solve single handedly, and one that Santana is reminded of almost daily in her ward as she spots the decade-old warning placards the Hispanic Alliance fixed to the front door of ailing homes after her tour.

“It’s always a reminder every day, but we call the health department and they’re dealing with it; we call building and housing and they’re getting it into court,” Santana added. “But how do you force these families to leave? I have no backup for them.”

Additional federal funding like this summer’s city-sponsored home repair lottery using ARPA dollars would help, Santana said, but Cleveland City Council needs more inroads with federal agencies to request government assistance.

“I don’t think people know how to (seek) federal funding,” she said. “I don’t think people know how to contract and build better relations.”

Margolius seemed to agree on the federal funding piece.

“There are estimates out there that say, for what we need to do for our housing stock in Cleveland, we need billions and billions of dollars,” he said. “Today, we don’t have billions and billions, but there are funds out there that have not been spent… We’re not doing enough if we’re not improving the housing stock. No local municipality (has that amount of money) but the federal government does.”

As the city maneuvers money and people to revise its strategy, LSCC and CDPH employees will continue waging war against Cleveland’s lead pollution on the information front.

Closer to zero

While any bloodstream lead presence can contribute to lead poisoning, potentially causing reduced intelligence levels and a host of physical issues, the City of Cleveland pays the most attention to cases where children test at 10 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood or more. It’s in these cases that the CDPH begins issuing citations and the Cleveland Department of Building & Housing taps the Cleveland Housing Court to prosecute landlords.

Before that, however, CDPH positions itself as an informational, upstream watchdog, fielding educational materials to families whose children test in the range of 3.5 to 9.9 micrograms per deciliter.

“What we’re trying to do is see what we can do to get the word out to the families,” said Etoi Young, who manages CDPH’s Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program. “We’re trying to up our marketing to get word out to the community more, because the preventative work that we do is to not have a kid come in and test positive.

“We get all the kids that test positive, so we want to catch it before it gets to that point…Even getting them into their provider to talk to their doctors and nurses in the facilities as well. Our work is to have zero kids test positive but we need to get the houses together as well.”

Whether the solution is some new collaboration between Cleveland departments that oversee public health and building code or more federal funding, a change in testing and removal procedures will have the most immediate impacts to the city’s lead removal standards.

Young said lead appraisals at the beginning and end of the removal process can grow expensive depending on the property in question and the extent of the work it needs.

HomeGuide prices the average initial lead assessment up to $1,500 while LSCC averages the clearance test between $250 and $500 for Cleveland property owners. Those costs often come bundled with a high price tag, sometimes up to $20,000, to perform temporary DIY or permanent, contractor-assisted lead abatement practices.

Stripping doors, windows and other common household features of lead paint requires careful hands and a knowledge of chemical exposure, two areas that LSCC teaches via its lead safe worker programming.

As the City of Cleveland organizes data and recommendations from internal departments and external partners, multiple organizations like LSCC have taken it upon themselves to offer two-pronged approaches to rectifying interconnected living problems. Until further legislation or recommendations materialize, it’s difficult to predict what resources and strategic changes the city needs to employ to remove lead from owned and renter properties.

Simultaneously, it’s obvious to the engaged stakeholders that heavily intertwined issues of housing quality and health responsibility, the majority of which predate lead awareness in Cleveland, will require several-pronged solutions to untangle.

“It’s definitely a staffing issue, it’s a technology issue, we have issues with contractors,” Cheairs listed. “How do you attract people to building and housing? Is there a pay equity issue where suburbs ad paying people a bit more than the City of Cleveland is? Multiple issues here are conflated, and you (have to) think about the start of this program during the pandemic. . . I intimately know how hard it is to enforce (housing rules) en masse, especially when you have thousands and thousands of people who are not adhering to the law.”

Clevelanders who are experiencing difficulty with lead-infested homes can reach out to CHN Housing Partners’ (formerly the Cleveland Housing Network) Lead Program in collaboration with LSCC at 844-614-5323 or lead@chnhousingpartners.com to learn if they’re eligible for remediation assistance.

The Lead Safe Cleveland Coalition hosts free training sessions designed to teach property owners and landlords as well as independent contractors how to renovate properties into lead clearance out of its Lead Safe Resource Center.

Readers interested in following Cleveland’s soon-to-shift lead legislation can attend the Lead-Safe Advisory Board’s next quarterly meeting, open to the public at 1 p.m. on Dec. 12 in Cleveland City Hall, Room 509. At the time of the policy change announcement, Bibb also said the city would eventually upload lead certification data to its open data portal.

Keep our local journalism accessible to all

Reader support is crucial as we continue to shed light on underreported neighborhoods in Cleveland. Will you become a monthly member to help us continue to produce news by, for, and with the community?

P.S. Did you like this story? Take our reader survey!