Last week, Cleveland received its first heat advisory of the summer, caused by the heat wave blanketing much of the Midwest and Northeast. Due to the changing climate, heat waves are becoming hotter, more frequent, and longer, and cities like Cleveland experience even higher temperatures, records show.

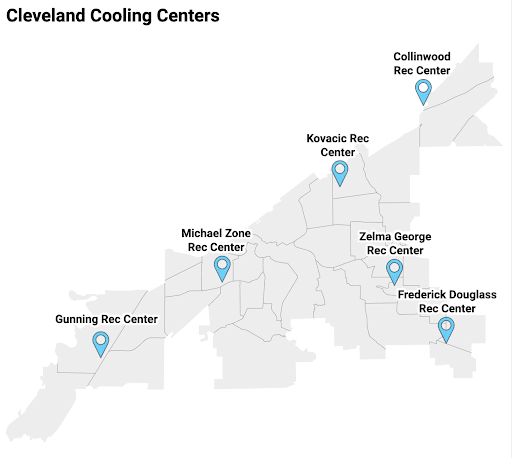

On Sunday, June 16, the City of Cleveland released information about its plan and schedule to open cooling centers “for Cleveland residents that are seeking shelter over the next week of 90 degree plus temperatures.” From June 17 to June 21, six Neighborhood Resource & Recreation Centers opened from 11:30 a.m. to 10 p.m. for people to relax and cool off.

Cities like Cleveland experience higher temperatures due to the urban heat island (UHI) effect. Urban infrastructure, such as buildings and roads, absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat more than natural landscapes, such as forests. In urban areas with highly concentrated infrastructure and limited greenery, daytime temperatures are about 1-7°F higher than in more rural areas.

According to the EPA, there are steadily increasing warming trends in many areas of the United States, and heat waves are occurring more often than ever. Children growing up in Cleveland today will experience four more heat waves per summer than those who grew up here in the 1960s. Heat waves are also, on average, a day longer than they were in the 1960s.

The effects of heat waves are not felt equally. Josiah Quarles, director of Organizing and Advocacy at the North East Ohio Coalition for the Homeless (NEOCH), works with people who are unhoused or experience housing insecurity. “It’s extremely dangerous [when] folks don’t have the benefit of air conditioning,” Quarles emphasized.

During extreme heat, NEOCH’s staff must prioritize supplying water and information about places to cool down to Cleveland’s most vulnerable populations. “The city lacks ample public water fountains, so dehydration is a serious risk for vulnerable populations,” Quarles said.

Quarles also mentioned that people in insecure housing situations and lower-income households often do not have functioning air conditioning. “A lot of folks may not even have electricity,” he added.

As many as 15% of homes in Cleveland have no air conditioning. Even with air conditioning, low-income households face higher costs due to the likelihood of living in older, less insulated homes. According to the US Energy Information Administration, energy-insecure households paid 20 cents more per square foot for energy usage than the national average. The longer and hotter summers are increasing the costs of cooling homes, making it more difficult for low-income households to afford air conditioning.

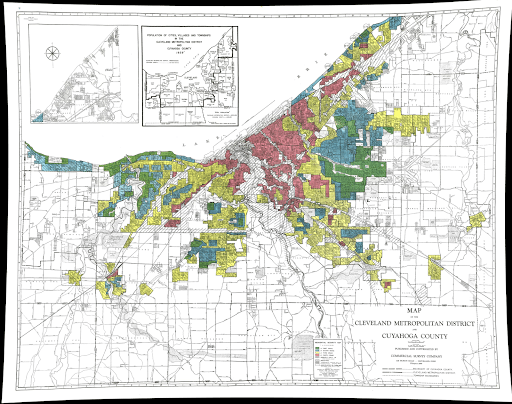

Further, cities feel the impacts of the UHI effect block by block, with some neighborhoods feeling much hotter than others. Neighborhoods that are poorer and have more residents of color can be 5 to 20 degrees hotter in the summer than wealthier, whiter parts of the same city. The UHI effect disproportionately impacts marginalized communities due to infrastructure, greenery, and resource disparities.

A 2020 study found that formerly redlined areas consistently face disproportionately higher temperatures in 94% of the 108 cities it included. The study linked urban heat islands to the legacy of discriminatory urban planning policies. The researchers argue that global climate change will further exacerbate historically codified inequities in the US.

In Cleveland, it’s not hard to understand why some parts of the city are hit harder by heat waves. Green spaces are consistently more abundant in wealthier and whiter neighborhoods. Lower-income neighborhoods are often located near expansive roadways and large building complexes, which retain and re-emit heat, raising temperatures in surrounding neighborhoods throughout the day and night.

Extreme heat is not just an inconvenience. It can have detrimental, and even deadly, impacts on people’s health. An Associated Press analysis found that 2023 set the record for heat-related deaths, and according to a study from Yale University, heat wave mortality increases by almost 2.5% for every 1°F increase in heat wave intensity.

People who are the most exposed to the heat are often the most vulnerable to heat-related injuries. Older people have the highest risk of heat-related injuries and deaths. According to Quarles, “We are seeing the highest increase in our unhoused population is with elderly folks as they can’t keep up with inflation and rising housing costs due to fixed incomes.”

High temperatures and humidity pose significant health risks for individuals with high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes. In Cleveland, over 40 percent of adults have high blood pressure, which is about 10 percent higher than the national average. According to University Hospital researchers, redlined neighborhoods have higher rates of cardiovascular disease.

Vulnerable populations need support from the city during extreme heat, but staff from the six cooling sites reported slow days with very few people utilizing the AC and water. Workers from the Collinwood Rec Center said even their busiest day saw only a dozen people trickle in.

A Frederick Douglass Rec Center staff member noted that the cooling centers weren’t advertised enough. “Not a lot of people know about it,” she said.

Quarles argues that emergency cooling centers cannot solve people’s vulnerability to extreme heat. “When you’re trying to solve a symptom of the problem in a day or two days, you’re not going to be able to reach everyone, you’re not going to be able to find everyone, and communicate information to everyone,” he said. “Emergency tactics can never meet the need.”

Quarles expressed that he’s glad the cooling centers exist for those who can take advantage of them, but they are not a comprehensive or sustainable solution to extreme heat. He suggests that Cleveland consider the root causes of people’s vulnerability to extreme heat.

He said ensuring every Clevelander’s safety during extreme weather “starts with ensuring that everyone in Northeast Ohio has safe and secure housing.”

Keep our local journalism accessible to all

Reader support is crucial as we continue to shed light on underreported neighborhoods in Cleveland. Will you become a monthly member to help us continue to produce news by, for, and with the community?

P.S. Did you like this story? Take our reader survey!