Relatives of Tanisha Anderson partnered with Cleveland City Council members and Case Western Reserve University students to author a new piece of legislation. As proposed, “Tanisha’s Law” would revise training regimens for mental health crises via a new Department of Community Crisis Response. This new team would try to prevent incidents like Anderson’s November 2014 death, which occurred after Cleveland Division of Police officers detained her while responding to a mental health emergency at her East Side home.

On Nov. 12, 2014, Cleveland resident Tanisha Anderson took her last breath shortly after uttering The Lord’s Prayer while in the custody of two Cleveland Division of Police (CDP) officers amidst a panic attack. Lying on the ground, cuffed, with her dress pulled above her waist, Anderson hallowed the name, requested the daily bread and – within minutes of leaving her Hough home in a squad car – breathlessly died in what the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s Office labeled a homicide.

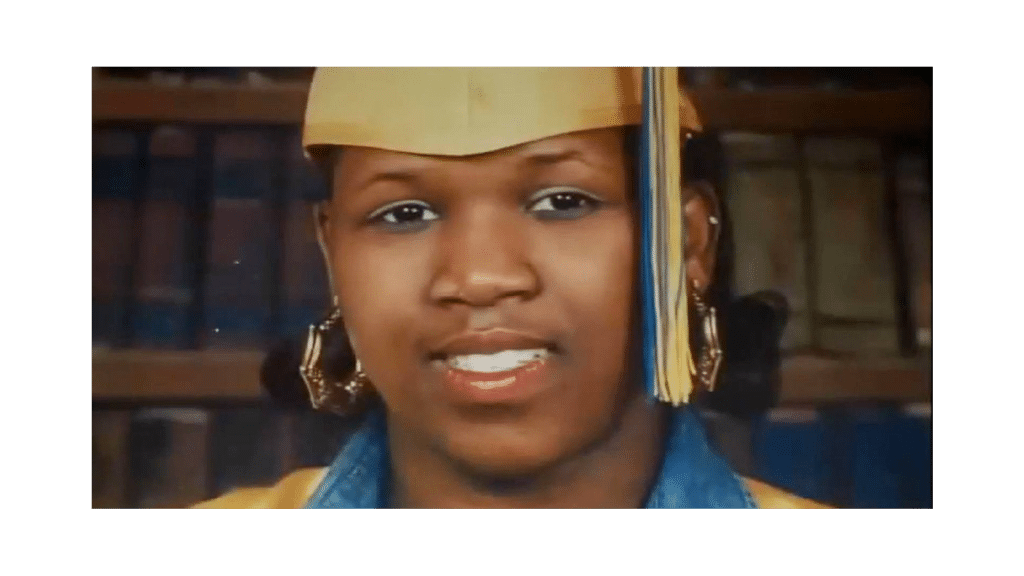

Nearly a decade after the incident, Tanisha Anderson’s family members, Cleveland City Council and advocates from Case Western Reserve University’s (CWRU) Student Legislative Initiative of Cleveland (SLIC) introduced “Tanisha’s Law” in November to preserve the 37-year-old’s legacy while affecting change.

Councilmembers Stephanie Howse-Jones, Rebecca Maurer and Charles Slife first read and proposed Emergency Ordinance No. 1198-2024 at City Council’s Nov. 4 meeting. It’s described as a coordinated effort to remove Cleveland police from nonviolent mental health emergencies and revise officer training for response to violent incidents.

“They got her down on the sidewalk and tried to get her in the car,” Michael Anderson, Tanisha’s uncle who has been publicly championing the law, recalled during a recent interview. “She wasn’t going for it, so they pulled her out and put her on the ground and cuffed her. When they picked her up and threw her down, the dress stuck up. Until Tanisha’s law is passed, she’s still on that sidewalk, 90 percent unclothed.”

The CDP ultimately issued a 10-day suspension in 2018 for the responding officers’ participation in events that have left the Anderson family confused for 10 years. The four years after Tanisha Anderson’s death saw separate investigations progress from the Cleveland Police Department, to the Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s Department, to the Ohio Attorney General’s Office, to a county grand jury, which acquitted the officers.

In response to a request for comment from The Land to the CDP, a communications official in the Mayor’s Office said the City of Cleveland is unable to comment on matters that may have legal significance, including laws currently cycling through City Council.

Anderson said he sees the law, and the buzz surrounding it, as a way to make sense of the years of mistreatment he believes Tanisha’s case has received from the media as well as law enforcement agencies and the court system.

Per Cuyahoga County’s decedent database, medical examiners pronounced Tanisha Anderson dead on Nov. 13 from “a sudden death associated with physical restraint in a prone position in association with ischemic heart disease and Bipolar disorder.” Her family rejects the assertion that Tanisha had ongoing heart issues. They also feel her homicide was overshadowed in the 2014 news cycle due to its proximity to the well-publicized police killing of 12-year-old Tamir Rice the following week, which received more attention than Tanisha’s death due to the victim’s age and the presence of surveillance footage of the incident.

Michael Anderson said Rice’s death ought to retain prominence as an example of gross police misconduct, but hopes by resurfacing Tanisha’s story that Clevelanders can get better and safer mental health responses through the newly proposed legislation. As Tanisha’s uncle sees it, her death was stripped of relevance because it occurred on the opposite end of town from Rice’s death, going unfilmed at a private residence.

“I have so many emotions when it comes to how my niece left this Earth,” Anderson said.

Michael Anderson was not residing in the same Hough duplex as Tanisha at the time of the death, but preserves a timeline of events using information pulled from speaking to family members like Tanisha’s mother, Cassandra Johnson (who died in 2021) and by consulting the police reports he carries in a thick envelope marked “Tanisha’s Law.”

The report states Tanisha’s family first decided to phone Cleveland dispatch shortly after 8 p.m. to request medical attention as they grew concerned and confused watching their relatives habitually flicker light switches at their shared Hough neighborhood duplex. An ambulance never arrived; instead, the city sent two officers who stayed for a brief period. Once the initial responders had apparently determined Tanisha was not posing any threat, they left.

Family members at the Hough address made a subsequent call to dispatch around 10:45 p.m., informing authorities that the 37-year-old had exited onto the porch, wearing the sundress she customarily used as a night gown, in order to wash the windows. Tanisha’s relatives requested EMS support, expressing concern that Tanisha would become ill walking outdoors shoeless in temperatures that bottomed out around 28 degrees.

In response, dispatch sent a separate set of CDP officers to investigate: Scott Aldridge, a detective, and Brian Meyers, Aldridge’s partner, who decided upon arrival to take Tanisha to St. Vincent Charity Medical Center for a psychiatric evaluation. Tanisha agreed and cooperated until she saw the police car; she then became upset and refused to go.

At that point, Anderson and the police report agree that officers tried to force Tanisha into the car; when she refused, they brought out handcuffs and tackled her in an attempt at restraining her.

“It was November, so the ground was cold,” Anderson added. “Officer Scott Aldridge had his knee on her back… and he’s (talking to the) family members. She started saying the Lord’s Prayer, not realizing she was losing her breath. I don’t know if she said ‘I can’t breathe.’ … She was overweight, and when you are (lying) down like that and someone’s got their knee on your back, something’s going to happen where your lungs won’t open up.”

Officers Aldridge and Meyers ultimately kept Tanisha Anderson on the sidewalk for what Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s Department investigators later determined was over 20 minutes, as revealed in a report from the Ohio Attorney General Special Prosecutions Section. An EMS crew arrived on scene at the CDP’s request and decided to transport Anderson to the emergency department at Cleveland Clinic

Little is known beyond that; the family members who had watched her enter the ambulance weren’t permitted inside the vehicle, having relied since then on personal intuition and secondhand reports to piece together what occurred inside the ambulance over the last decade.

Since then, however, the Anderson family has strategically made presence online, speaking publicly and on camera; while Michael Anderson said the harm can never be undone, some of Tanisha’s dignity can be restored by helping others.

Beyond healing the Anderson family and enshrining Tanisha, Michael Anderson said the value in resurfacing the story of Tanisha Anderson’s death is to put pressure on Cleveland City Council to affect actual change, an outcome the family has been chasing for the past 10 years.

Painful legislation

Before it can be codified Ordinance No. 1198-2024, the law – as attributed to Howse-Jones, Slife and Maurer – must first run the gamut of City Council’s review process. After administrative review is complete, a committee will adopt it and hold hearings, likely taking place sometime in 2025. If it passes committee vote, Tanisha’s Law will then go to a final vote of Council.

The proposed law states individuals experiencing crises deserve “a humane response” to their situations by “connecting them with appropriate and timely care” – specifically the CDP’s Crisis Intervention Team (CIT), Cleveland’s Division of Emergency Medical Service, licensed clinicians and other Clevelanders who have experienced mental health and substance use issues.

It proposes that families seeking support would “have confidence that their loved one will not be placed in imminent danger.” Relying on behavioral health specialists to disentangle situations currently handed to police officials, the legislation aims to ensure crises are “addressed more safely, with greater impact, and [are] more cost-effectively and efficiently [resolved].”

The legislation would also create a new “Department of Community Crisis Response,” the director of which would work with Cleveland’s existing departments of public safety, public health, aging and community relations. According to Howse-Jones, seven city staffers had tentatively stepped forward to run the department when the law was introduced in November, but some cities have teams of 45 employees engaged in similar work.

The department head will also oversee a crisis co-response program, including an Unarmed Crisis Response team working alongside the CIT, and collect data for use by the city and Cuyahoga County. Cleveland Police would be required to mandate generalized crisis intervention training for all officers on the force, while volunteers who elect to become “Specialized” CIT members will receive “enhanced, specialized, crisis-intervention training” for crisis scenarios.

“We know that fatal encounters of Black women with police officers are significantly less likely to garner media attention or, certainly, collective outrage,” said Bryan Adamson, associate dean of diversity within CWRU’s School of Law. He spoke during a public ceremony that both honored Tanisha Anderson and examined police accountability in mental health response on the university’s campus.

“Black women and girls are more likely than any other group of women to be killed by the police… Black women have been killed by police in their homes, in their cars, in the company of parents, in front of their children,” he said.

Different decrees

A new law, city department and community response team will not alleviate the pain that has followed the Andersons since Tanisha’s 2014 death. Family members like Michael Anderson, as well as the CWRU law students who researched policing patterns for the ordinance, recognize that failing to implement changes will only lead to further unnecessary friction between law enforcement and mental health concerns.

“What the last 10 to 15 years have shown us in Cleveland is that we do have issues with how we respond to different calls, whether (they) be mental health crises or not,” Bobby Read said in an interview. Read is one of the several-dozen CWRU students to collaboratively research and prepare parts of the Tanisha’s Law package as part of the college’s Student Legislative Initiative of Cleveland (SLIC).

“There have been a number of people that have been killed by police in the Cleveland area. There have been a number of high-profile cases that have come out of incidents and, if nothing else, the Consent Decree shows that we have an issue with how we police here in Cleveland,” he added.

The U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division crafted the Consent Decree much like a top-down corporate restructuring. The decree came in response to an investigation that determined the Cleveland Department of Police “engages in a pattern of practice in the use of excessive force.”

In a cover letter to former Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson upon the decree’s 2014 release, DOJ officials stated that such practice violated the U.S. Constitution’s Fourth Amendment while creating “a rift between CDP and certain segments of the community it serves.”

The latter half of 2024 has seen city officials make progress with the Cleveland Police Monitoring Team (CPMT) that reports on CDP’s Consent Decree adherence to Northern District of Ohio Judge Solomon Oliver, Jr.

The latest CPMT semiannual report, which charts CDP’s progress toward achieving the Consent Decree’s standards, states CDP is in satisfactory compliance with three of four paragraphs in the decree’s settlement agreement, which lays out standards for officers on mental health calls.

The September 2024 report states Cleveland Police successfully followed the edict in improving its Crisis Intervention Program and establishing a Mental Health Response Advisory Committee. The committee looks to improve interagency communications between police and local nonprofits focused on mental wellbeing and manage officers on the intervention program’s Crisis Intervention Team.

The third paragraph of the decree stipulates a coordinator must rendezvous with the intervention program, as well as dispatch personnel. CPMT’s newest report states CDP is in compliance with this rule. The only area of the consent agreement that skirts compliance is a department-wide mental health resource program available to officers and other employees, but Cleveland’s decree will remain in place until the federal court that issued it decides all conditions have been met.

If Cleveland City Council does move to pass Ordinance 1198-2024, it is unclear if these other layers of oversight will be conducted in a different manner. It will be up to the City Council committees that are assigned to the legislation to iron out any wrinkles, but opinions differ as to how much headway has been made toward improving behavior that the DOJ said was “in violation of the Fourth Amendment” in the decree upon its 2015 release.

“I’m not sure how much the Consent Decree has progressed,” Read added. “I think I would be safe in saying this proposed legislation would help (CDP) be in compliance with some aspects of the Consent Decree because of the sort of training and responses required for mental health situations…

“I know a number of other cities have Consent Decrees, but this should not detract from the significance of being under (one). All of that, together, should speak loud and proud for why we need legislation like this to help alleviate stress on the police but also respond to calls that are nonviolent in order to give proper care and assistance.”

Personal for everyone

Councilwoman Howse-Jones, one of the law’s three sponsors, has personal ties that strengthen her support of the law.

“I am absolutely the kind of person who would have benefitted from having (better mental health) practices in the City of Cleveland, being a caregiver for a mother who is living with dementia,” she recalled. “…When I lived with her, again talking about 2013 and 2014, my mother probably contacted the police no less than 50 times.

“The police absolutely should not have been coming (to the house),” she continued. “For the most part, they would come to all of her calls and it would be the same argument between my mother and I about what I wasn’t doing and ‘Oh, she did this’ and ‘Oh, he did that.’”

While the police occasionally approached the door with a level of compassion, Howse-Jones said it would grow wearisome for her and the officers to sort out the same issue – sometimes for 15 minutes, sometimes for 2 hours. Now, as the department deals with worsening staffing issues, Howse-Jones said officers are often pressured into making quick judgment calls that determine residents’ fates.

As proposed, members of Anderson’s family and the Cleveland politicians supporting Tanisha’s Law believe it carries wide-reaching implications in a country that’s gradually shifting its law enforcement standards to address mental health concerns. For the SLIC members who researched community policing models involving mental health in other cities with Consent Decrees, the legislation has the potential to be that and more.

Students in their first year of CWRU law school founded the Student Legislative Initiative of Cleveland roughly two years ago, but Tanisha’s Law would be the first legislative measure the group proposes and helps ratify successfully. The group worked in 2022 to broach local and statewide efforts to mandate police body cameras and impose stricter limits on the qualified immunity status sometimes granted to officers in investigations of police misconduct, but Read said conservative pushback largely killed the effort at the Ohio Statehouse.

Since then, Read and other SLIC members have turned their attention toward advocating legislation in areas of individual interest. Read has been studying Greater Cleveland municipalities that have utilized conversion therapy, while other members have been positioning the group to take action in sealing eviction records and enacting a local Homeless Bill of Rights.

“I think a common trend for people who have been part of SLIC… is people realize, when they get to law school, just how unfair our justice system can be,” Read said. “There are so many different ways of being less fair to people who don’t have a voice in our government and in our justice system. That comes from systemic problems that have happened for so long that we just don’t have solutions to at the moment.”

In order to solve problems that its members consider wide-reaching, SLIC’s core body of 15 members envision and create research strategies that resemble systems themselves. Michael Anderson first reached out to Case Western seeking assistance in March of 2023; the school invited him for a visit that attracted students in political sciences, medicine and other disciplines outside of law. SLIC eventually formed a half-dozen different groups to draft the ordinance’s three sections. They hope their work can have lasting impact on a system that employs a much larger number of individuals.

“I think it’s clear from our research that there have been a number of successful (instances of mental health response) around the country,” Read added. “Yes, it takes money, but if we don’t put resources into this, then we’re not going to have positive changes to our community.”

Readers interested in learning more about the nationwide debate surrounding law enforcement response to mental and behavioral health crises can learn more via a January 2023 report from the American Journal of Public Health and resources from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Community Oriented Policing Services.

The African American Policy Network’s #SayHerName initiative explains more of the Anderson family’s story. Tanisha’s Law, proposed to Cleveland City Council as Ordinance No. 1198-2024, can be read in its entirety, with more information on Tanisha’s life and the proposed law offered in a recording of the public address held at CWRU’s School of Law Justice Center.

Those interested in learning more about the 2015 DOJ decree and its intended impact on local youth can consult Case Western’s “A Citizen’s Guide to the Cleveland Police Consent Decree.”

Keep our local journalism accessible to all

Reader support is crucial as we continue to shed light on underreported neighborhoods in Cleveland. Will you become a monthly member to help us continue to produce news by, for, and with the community?

P.S. Did you like this story? Take our reader survey!