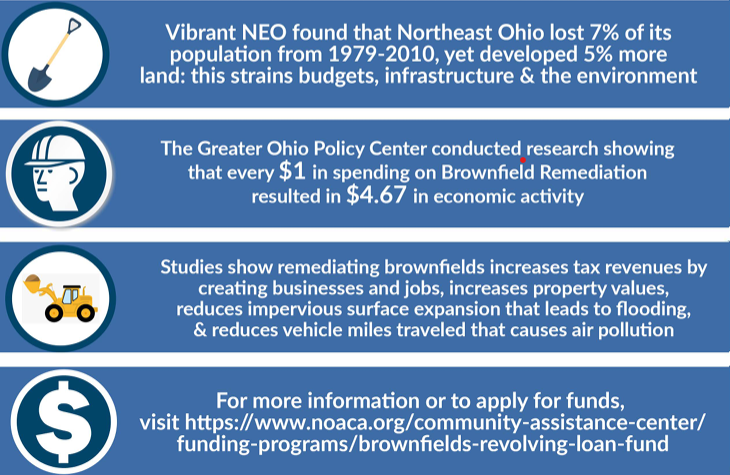

Vacant multi-acre parcels throughout Cuyahoga County are readying for redevelopment as brownfield sites – places of heavy industry where stakeholders are chasing the next Intel-sized tenant for the Cleveland market. As NOACA prepares to distribute over $500,000 in federal loans for new brownfield development in the coming months, land utilization policy experts discuss Northeast Ohio’s role in the nationwide brownfield development trend.

In October, the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA) will convene a board of 29 local development specialists to review proposals to use $500,000 in federal loans to begin developing pollution-tarnished sites. The organization’s brownfield planning committee will then determine which projects most deserve a portion of the land remediation money from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

“The reason (brownfields) are so important regionally is that the majority of these contaminated sites are in areas that, at one time or another, were very highly populated and have good infrastructure but also have sewer and water and electricity,” NOACA CEO Grace Gallucci explained. “They are areas that we want to invest in because the cost of overall infrastructure is lower than building in a greenfield.”

First announced in May to support NOACA’s Brownfields Revolving Loan Fund (RLF) program, Gallucci said the EPA’s latest $1 million infusion is part of a $300 million contribution to communities nationwide via multiple grant and loan programs at the federal level. The cash infusion comes roughly two years after the EPA tendered a previous $1 million to initiate the RLF as the NOACA/Vibrant NEO Brownfield Coalition in 2022.

That federal money joins the other funding pipelines that NOACA utilizes to distribute over $51 million in federal dollars on an annual basis. However, in this case a total of 12 counties beyond NOACA’s typical five-county service area are eligible. Applications for the forgivable loans closed on September 6, but more information on future funding can be obtained by emailing the coordinating agency.

The RLF is the same development initiative that has already squared away $1.3 million to scrub chemicals at brownfield sites at MLK Plaza on Wade Park Avenue, a former Sears store in Middleburg Heights and a defunct Firestone Tire and Rubber Company facility in Akron.

Gallucci stated that news of the new RLF funding arrives around the time Northeast Ohio developers are swiveling their heads toward Intel’s $20 billion investment into building a Columbus-area semiconductor plant. Experts say the production facility and its expected economic boon may have been a reality in Cleveland if more attractive redeveloped land had been available, as opposed to the untarnished Central Ohio farm land where the factory will likely sit.

One or more sites, as selected by NOACA before the end of the year, will receive attention from regional contractors and may become prime targets for developments of a similar scale in Cuyahoga County and its neighboring districts.

Brownfields as development engines

To hear brownfields described by Partners Environmental founder and owner Dan Brown, who helped author some of the original Ohio legislation geared toward brownfields in the mid-90s, is a far cry from actually visiting one of the fallow sites. Brown, who has worked in pollutant testing since founding his company in 1999, said the contaminated sites’ potential boils down to real estate recycling. “It’s as much an economic development tool as it is a regulatory and cleanup tool,” Brown explained.

Social consciousness and EPA guidelines have gradually nudged industries across the board to be more cognizant of the lasting polluting impacts of various chemicals. Brownfields, therefore, play a “two birds, one stone” role not always seen in commercial development.

According to Brown, the historical context of brownfields and the EPA’s remediation efforts are both connected to Cuyahoga County’s past. “The environmental industry started in 1970 with the Clean Water Act (amended in 1972). And you recognize that’s partially and not entirely responsible from the Cuyahoga River catching fire,” Brown continued.

The Clean Water Act was the first piece of federal legislation to give the EPA the authority to regulate pollutants. The agency later launched its Superfund program in 1980 in an attempt to completely reverse the scars of heavy industry. As Brown put it, “to make it as pristine as though Indian moccasins were the only thing that ever walked on it.”

The term “brownfield” first came into use in the mid-90s. Instead of decontaminating soil entirely, brownfield proponents asked, what if we could merely cover them up with a parking lot, a garage or some other thick surface that would keep humans away from the fallow dirt? It was a less attractive-sounding but more inexpensive concept than the Superfunds, with costs lying somewhere between unchecked pollution and EPA-ordained cleanliness.

“It’s taking into account the actual risk to receptor to determine cleanup,” Brown explained. “So the challenge around brownfields is, if we took a risk-based approach and studied (brownfield sites) adequately, can we put them back into useful life, back into revenue, back into economic viability? Won’t that be better, even if they’re not pristine?”

That’s where NOACA and the Cuyahoga Land Bank (CLB) join the fray, the former officiating the marriage of public policy and widespread environmental concern by doling out forgivable loans and the latter playing the role of matchmaker in land acquisitions.

Coordinating cleanups

In administering roughly $500,000 of the latest $1 million via the EPA (an exact match with the $1 million lending power the agency gave NOACA upon forming the NOACA/Vibrant NEO Brownfield Coalition in May of 2022) Gallucci said her organization is acting as an extension of the federal government.

“What we do with the county and city, we work in the state too,” Gallucci explained. “We work in tandem because some of our funding can be used as a match … If you are going after brownfield remediation at the state level, there’s a match requirement. You could use our funding as that match, as a way to level capital.”

National funding for brownfield projects, like other publicly accrued development capital, is eligible for capital stacking, a process that allows developers to employ multiple funding sources, like state programs and local initiatives, in conjunction to help close land purchases. That ultimately sweetens the deal for developers who wish to pursue multiple loans from the other organizations who join NOACA in managing Northeast Ohio’s polluted properties.

“We have access to the largest amount of money statewide for brownfield remediation,” said Adam Stalder, director of community stabilization at Cuyahoga Land Bank. “So it just makes sense that we … start thinking about being a clearinghouse for brownfield activities in the county.”

Stalder said strong examples of existing brownfields work could be found in projects like the Brooklyn Solar Farm atop the City of Brooklyn’s former landfill, the Steelyard Commons shopping center where various chain retailers occupy a former steel mill site and efforts to replace the former train tracks at Collinwood Yards with some sort of new infrastructure.

Land banks, Stalder continued, are a relatively new trend in the equitable redevelopment field. They’re meant, in part, to respond to the 2008 housing bubble, but, in 2009, Cuyahoga County became the first county in the state to designate a third-party vacant land manager outside of government purview. The Cuyahoga Land Bank has since used that head start to tear down 10,000 unused buildings and redirect the land for more opportune uses.

“As residential areas have been getting cleaned up, we’ve really made an impact over the last 15 years,” Stalder explained. “We recognize that houses still need to come down but that’s going to be less and less of a priority for us. What we do have … we’re a legacy industrial city. So we had a lot of really heavy industry … Now we’re thinking ‘these are developable sites. They’re in good areas.’”

The Heights site

The roughly 21,000 commuters who traverse Pearl Road in Middleburg Heights each weekday come close to the wedge-shaped Southland Shopping Center. Bracketed by Pearl Road to the north, West 130th Street to the west and Smith Road to the south, the Southland Shopping Center is now half-hollowed That’s despite its status as the “biggest shopping district” in a city of over 16,000 residents, according to Middleburg Heights Economic Development Director Charles Bichara.

Before any developers can replace the former Middleburg Heights Sears on West 130th Street, however, Bichara said two buildings have to go. Asbestos from floor tiles, drywall and other common building materials now hovers about the 168,000-square-foot store, which has remained vacant since shuttering in 2017. Ditto for the adjacent former Sears Auto Center, a 30,000-square-foot, 10-bay garage that Carvana briefly used as a staging lot until 2022.

Until 2021, Sears repurposed the main store’s 40,000-square-foot basement as a customer service call center, but the buildings are structurally obsolete, according to Matt Hammer, a principal with Civil & Environmental Consultants, Inc., which tests for contaminants in sites like the Middleburg Heights Sears.

“The attractiveness of this site … is that the infrastructure’s here,” Bichara stated. “It’s in a commercially viable corridor, that’s why it was built here in the first place, and there’s businesses here in the area that support it and the population.”

Bichara came to the same conclusion that other developers had about brownfields, according to Partners Environmental’s founder Dan Brown. As former industrial or commercial strongholds, they’re already interwoven into the transportation fabric of the community.

Hammer comes to a different understanding, in part based on asbestos grading that Sears and Carvana performed on site prior to vacating the building, which will need to face demolition before any new structures can claim its place. “(Asbestos is) going to be in things like ceiling tiles and floor tiles, maybe some of the glue on the floor tiles,” Hammer said. “You might have asbestos in the wall material sometimes. With that characterization, the city – with the help of contractors – is going to develop specifications written for abatement and demolition.”

Sometime this fall, Middleburg Heights will hire consultants to prepare and release an asbestos abatement report laying out what steps will need to take place before building demolition can begin. The report, per Bichara, will lay out a road map for remediation standards and, ultimately, determine the price any purchaser would have to pay.

At that point, a competitive bidding process will begin to determine who will be responsible for the work. Separate crews will need to be hired for abatement of asbestos and other materials (Hammer said contaminants like light bulbs and batteries fall into a “universal waste” category due to their ubiquity) as well as demolition and, eventually, new construction.

Man hours accrued via all the extra testing will increase price tags, but Stalder said Northeast Ohio developers need to foot such bills to harness land.

Columbus appears more attractive to companies like Intel, he continued, because of an abundance of ready-to-use space, but Cleveland can achieve new development without building on every square inch of the city. With planning and funding programs now getting funding at the local, state and federal levels, the real work will begin once developers or municipalities get commence with peeling back layers of rust and chemical-soaked soil.

“If we can redevelop these old industrial sites into new industrial sites, people can live closer,” he said. “If we don’t have to put extra strain on the road infrastructure, we don’t have to add lanes to highways. It makes more sense. I think that’s the way the world’s going.”

Brown seemingly agrees. Brownfield redevelopment, he said, can recontextualize pieces of scarred land without recharacterizing them, if handled propely. That old injection molding factory or former car lot may appear to be eyesores, little more than driveby stains abandoned across the Rust Belt, but Brown said communities can use modern policy to reorient them without dipping into tax dollars.

“(Brownfields) allow us to use the infrastructure we spent many years building,” he concluded. “Rather than pushing up greenfields, we can be redeveloping and using infrastructure right where people and jobs are. That’s why (brownfields are) so valuable … They allow us to bring a whole next generation of development to the table without having to overextend our infrastructure.”

Readers interested in learning more about support for brownfield redevelopment can email Brownfields@mpo.noaca.org for more on NOACA’s Revolving Loan Fund and other initiatives. Cleveland Mayor Justin Bibb also intends for some of the city’s American Rescue Plan Act to be used on brownfield cleanup via the Site Readiness Fund for Good Jobs Cleveland. The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency offers statewide funding through two programs of its own.

Those interested in gleaming a more generalized overview of brownfields in Northeast Ohio can review an EPA report on Cleveland’s brownfields or learn about the annual Ohio Brownfield Conference by exploring the Greater Ohio Policy Center’s brownfields redevelopment website.

Keep our local journalism accessible to all

Reader support is crucial as we continue to shed light on underreported neighborhoods in Cleveland. Will you become a monthly member to help us continue to produce news by, for, and with the community?

P.S. Did you like this story? Take our reader survey!