In 2021, I applied to be part of the Neighborhood Leadership Development Program because I wanted to contribute to my Glenville community – to be a leader. I knew from my neighbors and community meetings the inequities and frustrations that residents were experiencing on an everyday basis, and I wanted to learn how to make a difference.

Hundreds of community residents have come through the Neighborhood Leadership Development Program (NLDP), which empowers leaders in Cleveland’s inner-city and suburbs, since it was founded 15 years ago. Under the direction of former Cleveland Mayor Michael White, NLDP recruits 20 new community leaders every September in cohorts that meet on Saturdays over several months until graduation in April. The goal is that over the course of the year, participants work towards projects in their communities – in my year, these ranged from organizing music festivals in Slavic Village to curbing gang violence in Glenville. Past graduates continue to do amazing things.

Due to Covid, NLDP was forced to cancel the 2020 program. “The impact and success of the program is due in large part to its very interactive and interpersonal nature,” said Sandra Kluk, NLDP Program Administrator. “The negative impact of trying to do a whole program year remotely was too significant and the decision was made to postpone the Cohort XIV program year.”

I applied for a spot in Cohort XIV of NLDP with high hopes, but I found that the challenges of Covid continued, and they weren’t the only roadblock to success. Over the next few months of social distancing and a revised curriculum that precluded community field trips and restricted outdoor activity, one member quit the program over “pedagogical differences” and another beloved student disappeared inexplicably for a few sessions before it was announced that she had died. Nevertheless, in the end I found that despite the challenges of the year, NLDP was still able to offer valuable community leadership guidance to me and other participants. The pandemic made – and continues to make – community-building more difficult everywhere. We had to do our best.

High hopes

During my NLDP applicant interview with Mayor White and NLDP Assistant Program Director Julia Ferra, I was asked why I wanted to be a leader in my community of Glenville. I had prepared for this question, but when I began to talk about the disparities in services for much of Glenville’s population, my voice cracked and my eyes filled with tears. I thought of my neighbors and the community meetings I had attended where so many residents aired frustrations with the challenges they confront every day, like inadequate street lighting and lead paint in their homes. I was sure I had blown the interview by crying. Several weeks into the program Mayor White, who invited us to call him Michael and who I found to be both sincere and commanding, told the class that we were accepted into the program because he “saw our hearts.”

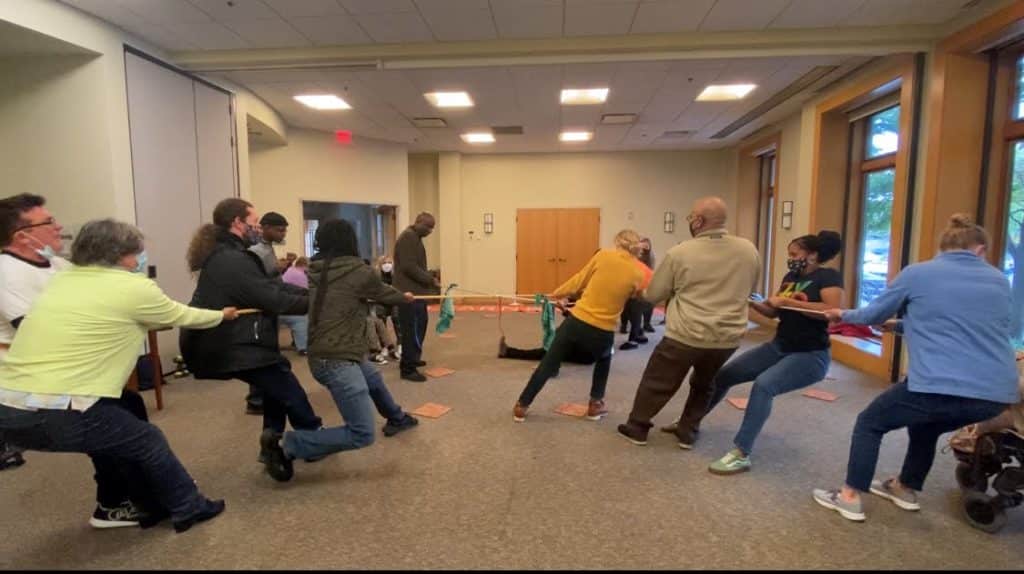

On the first Saturday class, 27 people, including seven coaches and program administrators, gathered at the Trinity Cathedral on Euclid Ave. in a 2500-square-foot room that comfortably seats 250 people, with thick wood beams, intricate chandeliers, and ceiling-high windows. As expected, my cohort of 20 students was a diverse group representing every neighborhood in Cleveland. We sat socially distanced at assigned seats and were each given a canvas tote bag containing a name tag, a table tent, and a copy of the book Becoming a Resonant Leader. Much later, I found out that the first session of the program is typically an ice–breaking ballroom dance lesson. As it did everywhere, Covid made everything much more distanced and difficult.

A slow start

The first sessions of NLDP were designed to break down inhibitions and to develop group trust despite the required distancing and face masks that set up a sense of isolation. Mayor White assured us that while the program was modified and that we would not be visiting any neighborhoods unless the situation with Covid changed; we would have the opportunity to add “tools to our toolbox” from various guest speakers whose presentations were often 6 to 8 hours long including breaks and lunch. I found it difficult to break down any barriers with masks, distancing, and sitting for such a long day. The reverberating acoustics of the room made it difficult to hear what was being said by both our cohort and the presenters.

“We missed out on a great way to collaborate and be well-rounded in our training,” noted Audra Jones who was new to NLDP and also the coach of my breakout group (referred to as a C-Pod). “My expectation was that there would be physical boots on the ground for our cohort, but Covid hindered our in-class connection and the chance to comprehend the community via physical presence in those communities.”

We were more than halfway into the program year when my classmate Adam Whiting suddenly quit. Adam, a musician, and community activist in Glenville, felt that NLDP didn’t deliver. “There was no plan for taking what we’ve learned and applying it,” he said. Recalling the first session when Michael White presented a physical toolbox as a symbol of what the cohort was to acquire, Whiting was frustrated with NLDP as a “lecture series that didn’t deliver the tools.”

Could it have been different?

My past experience with immersive learning (in yoga teacher training at Kripalu Center for Yoga in Lenox, Mass. and in vocal performance at the Cabaret Symposium at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in New London, Conn.) was that sharing hands-on experience often leads to deeper and perhaps lifelong relationships. But maintaining physical distance in the NLDP sessions, and with no community interaction, stunted our collaboration during the eight months we were together.

In hindsight, would NLDP have done anything differently about modifying the program due to Covid restrictions? “Not really,” Kluk said. “We spent a great deal of time going through plans to make sure we had strong safety policies in place for participants and having the opportunity to plan online sessions for graduates was a plus. We were very vigilant about the spread of Covid, and we were willing to adjust policies if there were changes to ensure everyone was as safe as possible.”

Several months after graduation from NLDP, a group of us gathered in the Harvard Community Services Center for a tree planting ceremony to celebrate the life of our departed colleague and friend Cathy Davis. Unmasked and huddled closely together outdoors on a chilly late October afternoon, the reunion of Cohort XIV included Mayor White, our coaches and fellow students. We paid a joyful tribute to Cathy’s deep commitment to her community. Afterwards, I thought back on Cathy’s humor, smile, and dedication to uplifting the lives of others.

Reflecting back, I can see just how hard it is to build community, especially with barriers like Covid. But perhaps we had connected as a class more than I had remembered under the cloud of Covid. Despite the restrictions, and the revised curriculum, upon reflection I realize that I have gained enough tools to launch my community website project for the Glenville neighborhood with hopes of inspiring civic engagement and addressing the problems in my community. This is what brought me to NLDP in the first place. Knowing that I will have lifelong access to my cohort and our guest presenters has helped me have a greater appreciation for what NLDP has to offer.

Dane Vannatter was a participant in The Land’s community journalism program.

We're celebrating four years of amplifying resident voices from Cleveland's neighborhoods. Will you make a donation to keep our local journalism going?

![Lakewood High School students organize walkout to protest ICE [photos]](https://d41ow8dj78e0j.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/12155714/DSC_3775-800x600.jpg)