The Judith Cafe, Cent’s Pizza + Goods, Table for Two and Imposters Theater are just a few of the businesses that have opened in the last few years on Lorain Ave. on Cleveland’s near west side, joining a slew of others that have opened over the past decade or so. The area is quickly being swept up in the tide of development, with more to come – but could a long-planned $30 million streetscape, including protected bike and pedestrian lanes, help or hurt this on-the-comeback commercial district?

That depends on who you talk to about the 1.8-mile project on Lorain from West 65th Street to West 20th Street. Everyone acknowledges Lorain needs a makeover. The pothole-worn stretch of asphalt has one lane of parking on each side of the street. Still, drivers often exceed the speed limit, treating parking lanes as driving lanes and endangering pedestrians and cyclists. Advocates have spent over a decade planning bike lanes protected from traffic by concrete curbs, as exist in Pittsburgh and other cities, but the project remains underfunded. Meanwhile, business owners are fretting over losing as many as 200 parking spaces along Lorain Ave.

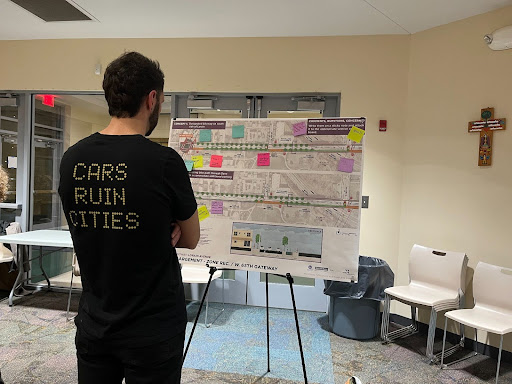

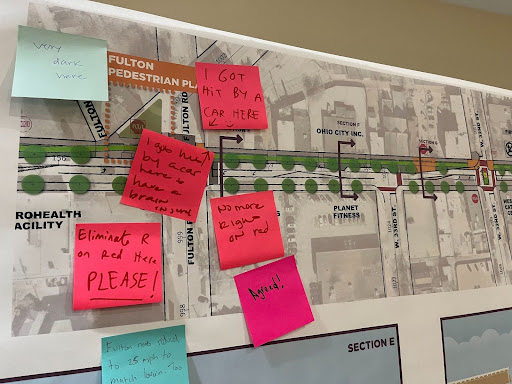

“Re-engineering Lorain to work for all modes of transportation will allow those who want – and more importantly, need – to move by other means to do so safely,” Jacob VanSickle, executive director of the advocacy group Bike Cleveland, told The Land following a January open house intended to gather feedback for the project attended by more than 100 people. “Once complete, the improved streetscape will allow the surrounding neighborhoods to reach the merchants and services along Lorain without needing to use a motor vehicle for a short trip.”

Yet Mike McBride, a developer who owns two buildings on Lorain, said he’s worried about the loss of parking spots. He said the number of businesses in the area has grown, and they need street parking. “My concern was, somewhere, it was decided to prioritize public transit and pedestrians on Lorain, which I think is great, but I don’t think they’re accommodating all modes of transportation, which include driving here,” said McBride. “What I’m not saying is these bike lanes are dumb and bad for driving. What I’m saying is if you’re flexible you can fix everything.”

McBride’s interest in the project dates back to 2017, when he co-authored a letter to the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA), a regional transportation planning agency that has supported the Midway project, proposing modified lane widths that would grant cars 11 feet of leeway traveling in both directions, allegedly allowing for seven-foot parking spaces on either side of the thoroughfare. This would allow for an eight-foot-wide bike lane along the center or one side of the street.

The other name on the letter belonged to Jeff Speck of design firm Speck Dempsey, who published his award-winning book “Walkable City,” a treatise on the positive urban impacts of multimodal transportation, in 2012. Now an international advocate of weening cities off cars, Speck proposed an idea that contradicts the National Truck Network’s suggested 12-foot lane widths as identified in a Cleveland-made project overview. The letter also cites ten-foot-wide travel lanes found alongside seven-foot parking lanes on East Ninth Street in Downtown Cleveland.

Calley Mersmann, Cleveland’s senior strategist for transit and mobility, responded to McBride’s concerns by saying the city is working to minimize impacts on small businesses that currently rely on on-street parking, such as those concentrated around Fulton Ave.

There is currently no construction date for the Lorain Midway. The city has been working with community groups since 2011 to plan and gather support for the project, but they still only have about half of the $30 million they need. They’re seeking the rest through federal grants and still hope to start work on the project next year.

Loss of parking spaces

In a parking study from Chagrin Valley Engineering, the city found Lorain’s maximum parking occupancy maxed out at 44% on Saturday, the street’s busiest day. According to McBride, however, the consultants failed to interview individual stakeholders like him and did not address why people are parking in specific spots, where they came from, and where they’re going.

VanSickle disagrees. He shared a slew of data from other cities that have embraced bike lanes within their transportation networks. He and Cleveland city officials pointed to the success of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail, a protected bike trail that has become a citywide attraction, and a retail sales hike on a six-block stretch in Salt Lake City where businesses cut street parking in 2015. Mersmann commented that an early overlay from Cleveland planners shows specific spots that would be lost to the project.

NOACA awarded the citywide Midway project $19.6 million (to be used on two Midway routes, Lorain and one in Midtown) after studying protected route plans in 2017. City engineers will use plans to bid on a piece of the $1.2 trillion set aside by the federal government as part of 2021’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. In addition to the protected bike lanes, the project would also add park-like green spaces, redesigned bus stops, and green sewer infrastructure to Lorain. These are opportunities to boost the city’s tree canopy, according to advocates.

“Cleveland has a vision for getting to a 30% tree canopy cover and these are opportunities to maximize that tree coverage,” said David Bass, coordinator of major transportation projects for the Cleveland City Planning Commission. “In addition, we’re just improving the aesthetic nature of the corridor and (its functionality). We’re thinking about where bike racks are located and putting in benches and other features along the roadway to make it comfortable.”

Getting in gear

For the Lorain Ave. re-do, Bass is partly responsible for coordinating between the city planning department and the engineers at the Mayor’s Office of Capital Projects. Also involved are Michael Baker International, a Pittsburgh-based design firm that also worked on the Opportunity Corridor project, and OHM Advisors, which is conducting civil engagement for the project as it did with meetings to redesign Lakeview Terrace and Middleburg Heights Central Park.

OHM will lead public engagement moving forward. The next question will be how small businesses will deal with a year-plus of construction. Andrew Worm, who owns The Judith Cafe at 5222 Lorain Ave. with his wife Jennie, said small businesses need to “band together to help each other out.” He’s worried about how construction could affect his business, and says that he and other businesses need city support during what will likely be a long construction process.

Worm and his partner previously owned the boutique Room Service on W. 25th St., and he recalled the negative impact of street construction on his business many years ago. “It’s understandable why you would get scared and why, coming from a top-down situation, someone tells you this is better for you, it feels a little patronizing, especially for people who are risking everything to open their business on a stretch of road that has mostly vacant storefronts,” he said.

If more funding is awarded, construction on the Lorain Midway could potentially parallel the Superior Midway, a similar project that will start downtown and stretch along a busy 2.4-mile section of Cleveland’s East Side. The Superior Midway is set to start construction in 2025, according to the current plans. Bike Cleveland hopes both projects will be embraced and then expanded across the city. Although advocates may disagree about the loss of parking spaces and other issues, most are on the same page when it comes to the city’s goal of creating safer, multimodal streets for cars, pedestrians and cyclists and working to eliminate traffic fatalities in the city of Cleveland.

We're celebrating four years of amplifying resident voices from Cleveland's neighborhoods. Will you make a donation to keep our local journalism going?