As part of the Cleveland History Center’s newest exhibit, “All Dolled Up: 200 Years of Dolls and Miniatures,” a private screening of the Netflix documentary “Black Barbie” was held for collectors and doll enthusiasts. Community Journalist Silk Allen, a doll enthusiast herself, shares her thoughts on the exhibit and the film.

I’m not really a doll collector in the traditional sense. Some collectors focus on vintage pre-war dolls, cloth or porcelain dolls, or modern fashion dolls like Barbie, LOL, and Bratz. They spend wild amounts of money on their collections, keeping them stored in pristine boxes, untouched and preserved. But me? I’m more of a doll hobbyist. I exclusively buy Black and brown fashion dolls like Barbie, Naturalistas, and Fresh Dolls. The minute I get them, I tear open the packaging, undress and redress them based on their “personality,” and give them names. From there, I assign them “roles” and take photos of them in homemade backdrops for my Instagram page. Not everyone goes this deep into it, but it’s always fun to connect with other adult collectors, hobbyists and doll enthusiasts.

In October, I met a other doll enthusiasts while attending the Western Reserve Historical Society’s (WRHS) newest exhibit, “All Dolled Up: 200 Years of Dolls and Miniatures,” at the Cleveland History Center. Curated by Patty Edmonson, WRHS curator of Costume and Textiles, the exhibit, according to the WRHS website, promised to “explore the themes of play and childhood and how dolls have the ability to elicit core memories.”

Mothers and daughters, aunts and nieces, sisters and play cousins were all dressed to impress at the opening of the exhibit and the private screening of “Black Barbie”, the Netflix documentary produced by Shondaland and directed by Lagueria Davis.

The film spotlights three trailblazing Black women—Beulah Mae Mitchell (one of Mattel’s first Black employees and the director’s aunt), Kitty Black Perkins (designer and creator of Black Barbie), and Stacey McBride-Irby (creator of the AKA Barbie and the So In Style line). Each played a pivotal role in bringing the iconic Black Barbie to life, highlighting the significance of identity and representation, even in imaginative play.

The screening was a fun and festive affair, complete with a beautifully decorated pink and red display table featuring popcorn, snacks, and candy surrounding a replica of the original Black Barbie from the film. Guests enjoyed two “Doll-icious Drinks” — a Sparkling Sunrise Mocktail and a Pomegranate Apple Cider Sparkler — served in cute plastic champagne flutes. An assortment of cheeses and crackers were laid out alongside decadent bite-sized cake pops from Nina Lau’Rens.

About 50 guests settled into the Junod Center to watch the film and then explored the exhibit afterward. Curator Patty Edmonson was thrilled with the turnout, saying, “People can watch the documentary at home, but this event has a community vibe. We don’t usually see Black women at our events.”

The documentary’s impact resonated across generations, uniquely touching each attendee. China Allen, (no relation to the author) visiting from Florida with her niece, shared a fond memory of the dolls.

“I played with Barbies until I was 15 or 16 because that was the only thing to do when I was grounded!” Allen said. She now prides herself on gifting Black dolls every year to the kids in her family.

Carisse Turner Smith from Garfield Heights explained that she has the limited edition Alpha Kappa Alpha (AKA) Sorority Centennial doll featured in the documentary and that she thought the film was amazing.

“It captured the thoughts and feelings I had growing up, the love of self, and my mom also only bought Black dolls. I’m passing that legacy down,” she said.

Not everyone in the audience was a collector, hobbyist or enthusiast, but they still enjoyed the film. Aniya Mims, 13, said, “It was very informative. I like history, I like dolls, but I don’t want them — I gave mine all away.”

Patty Edmonson, who curates an exhibit at Western Reserve Historical Society annually, often begins planning events six months to a year in advance. She was inspired while organizing the “creepy doll room” in the Center’s storage, saying she was particularly drawn to the clothing. Additionally, her two young daughters, ages 4 and 7, love miniature food and accessories, and the recent popularity of the “Barbie” movie in theaters last year further fueled her interest in showcasing dolls and miniatures.

For Edmonson, the decision to screen the “Black Barbie” documentary instead of the “Barbie” movie was an easy one. “We are an educational institution, and our mission is to tell the stories of our community,” she explained over email. “Although this is a national story, I’m sure many people in Cleveland can connect to the film and its themes.”

Another circumstance that led to this particular event was the donation of Cleveland doll collector Ranell Gamble’s estate to the institution. Gamble, who passed away in 2020, willed her collection of mostly Black dolls, including 20 Black Barbies, to WRHS. Interestingly, the former attorney didn’t receive her first Barbie until she was 38 years old, in 1980, when Kitty Perkins Black created the Black Barbie. She became a dedicated collector. Gamble had been a member of the Cleveland Doll Club, the Northern Ohio Doll Club and the United Federation of Doll Clubs. A childhood photograph of Gamble with a doll is on view in the gallery, along with stories and photos of other doll owners that lived in Northeast Ohio.

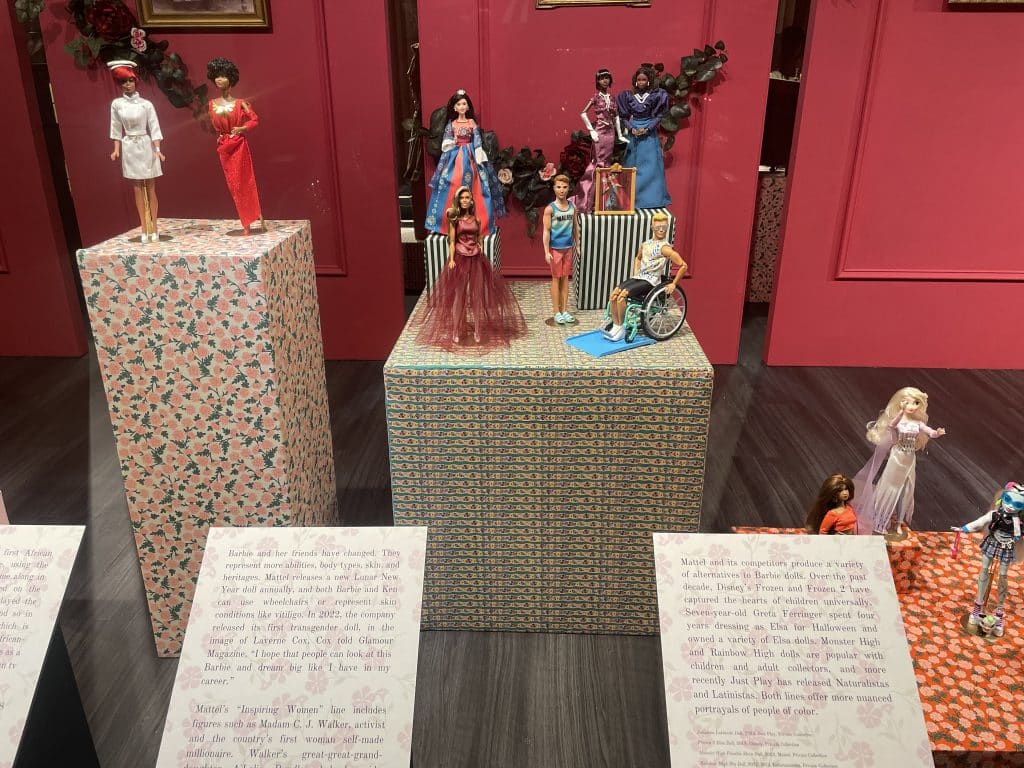

As soon as you walk into the Chisholm Halle Costume Wing, viewers are treated to a fun visual history of individual children and the way they’ve connected with dolls and miniatures over the past 200 years. The dolls in the gallery are displayed next to life-size fashions, historical images and toys dating back to the 1830s from the WRHS collection.

You learn about local doll enthusiasts, like Shaker Heights resident Cathy Lincoln, who creates custom miniature rooms based on real homes that she’s seen in her world travels. Her Barbies, the tattoo parlor room, the Addy doll, and nun doll are all currently on display. There’s also the photograph of a doll belonging to a young Cora Douglass, born in 1859. She grew up in Gallipolis, Ohio, a location where residents had access to imported goods such as dolls and held the first Emancipation celebration in 1862.

As they explore, patrons will also learn historical news about Ohio and its society — families with the money and means shopped at Levy & Stearn, the fancy goods store known for selling dolls, dolls houses and other toys — and how seriously mothers and daughters took tea time and furnishing a doll’s house and closet.

At the same time, guests will witness the complications of researching historical photographs and the reason why there aren’t that many Black children with Black dolls — Black dolls weren’t being manufactured. In the 19th century, most dolls of color were homemade and when toy companies did start to make them, they just tinted the existing products, which is another reason why Black Barbie was so important when she debuted.

At the end of the gallery is a play area with dolls, houses and accessories that kids and adults are encouraged to use to have fun and explore their imagination!

The exhibit runs from now until August 25, 2025.

Additional photos from the screening are below.

We're celebrating four years of amplifying resident voices from Cleveland's neighborhoods. Will you make a donation to keep our local journalism going?