One hundred years ago, a pioneering librarian opened a new flagship for the pioneering Cleveland Public Library.

Linda Anne Eastman, the nation’s first woman in charge of a big-city library system, led the creation of the $4.6 million Cleveland Main Library at 325 Superior Ave. Throughout the ensuing century, Main Library has offered world-leading collections, expansive services, an innovative layout, and the oldest open stacks at a major metropolitan library.

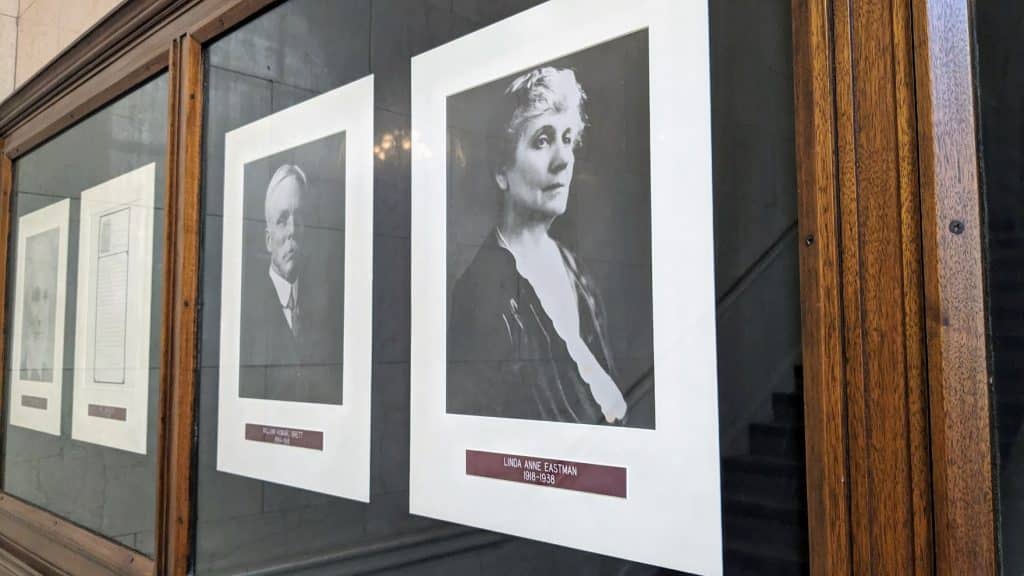

Main opened on May 6, 1925, seven years after a drunk driver narrowly missed Eastman but hit her superior, William Brett, who was carrying plans for the Superior Branch. Eastman, then vice librarian, or second in command, did not apply to succeed Brett. But the trustees unanimously promoted her over many male applicants.

A century later, library leaders consider all of this year’s public programs at Main as its centennial celebration. A highlight will be a festival from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. on Saturday, May 10, with an Alice in Wonderland-inspired Curious Garden Party, the unveiling of a historical marker, the debut of The Library Shop across the street, the reopening of the improved TechCentral and of the improved Eastman Reading Garden, music, refreshments, face painting, line dancing, laser engravings, and other attractions. Visitors are encouraged to register and to come dressed as their favorite literary characters.

Gentle and visionary

Linda Eastman spent 45 years at the library system, 20 at its helm. She helped expand CPL from 18 workers and fewer than 58,000 items to about 1,200 workers and more than 2 million items.

According to several sources, including a book on the history of CPL called “Open Shelves and Open Minds,” Eastman was small, blue-eyed, gentle, deliberate, plainly dressed, and modest except about her library. She promoted it tirelessly with speeches, articles, monographs, windshield stickers, bookmarks, movies, a campaign truck, and more. She became a professor at Western Reserve University’s library school and served a term as president of the American Library Association. She helped make Main and Cleveland Public internationally influential.

Cleveland’s library system began in 1867 as the Public School Library. It was already innovative by Eastman’s arrival. In 1890, it created the first open stacks in any big-city library. Instead of asking librarians to fetch materials, patrons could browse and discover for themselves. Eastman added many more innovations for students, summer campers, immigrants, blind people, hospital patients, travelers, businesspeople and general readers.

“A library should be democratic,” she told The Cleveland Press in 1918.

She was proud of Main. “Dignity, good taste, beauty and adaptability to its purpose combine to give it real distinction….” she wrote in Cleveland Trust Monthly, a magazine by the bank of the same name. “Each visit to this building should be a pleasurable incident with something new and interesting to see, to read, and to carry away.”

Others agreed. “One pauses breathless and awed at the loveliness, the artistry, the majesty of the building,” a Plain Dealer columnist gushed in 1925. “It is truly a great tribute to the shining light of learning, and free to all.”

A bibliophile from childhood

Eastman descended from Pilgrim commander Myles Standish. She was born in Oberlin in 1867. Never marrying, she lived most of her life with immediate family in Cleveland.

As a girl, she loved to visit the city’s tiny library, which moved a few times between upstairs spaces in different downtown buildings. One day she was told that a book she wanted for schoolwork wasn’t available. Overhearing, then-librarian William Brett promptly sent someone to buy the book for the visitor.

Eastman graduated from West High School with honors, took a course at Cleveland Normal, and taught public school on Cleveland’s West Side for a few years. She created the school district’s second classroom library. In summers, she worked at the library’s West Side Branch.

She came to feel that children learned more from books than classes. So she asked Brett for a year-round job. He warned her that she’d have to start at $1 per day, about half her pay as a teacher. She persisted, scored 98 on the entrance exam, and became an apprentice in 1892.

Soon Eastman was running Cleveland Public’s first branch library, which stood above a store on the Near West Side. Then she opened its second branch in Miles Park. She spent a year as Dayton Public Library’s vice librarian and returned to Cleveland in 1896 for a new job with that title.

In 1903, she started some of the nation’s first loans of Braille materials. She followed up with spoken records, free tickets to shows, and other services for blind patrons. She shared materials for the blind with libraries in 59 Ohio counties.

Eastman bought many materials in foreign languages and created an Americanization program at library branches for Cleveland’s different nationalities. She created the nation’s first public branch just for children before making room for them in the new Main.

She persuaded the New York State Library School to let her earn a two-year certificate through the mail. She later got three honorary degrees.

Making Main

Eastman helped pass two bond issues to finance Main, whose $4.6 million cost would equal about $104 million today. At the groundbreaking in 1923, a cornerstone was laid holding a time capsule, and former British Prime Minister Lloyd George spoke to about 3,000 listeners.

Main’s opening day drew a similar crowd. The five-story, roughly 250,000-square-foot building was designed by Cleveland’s prestigious Walker and Weeks in gray marble with a Beaux Arts style in keeping with downtown’s Group Plan. An Italianate courtyard added light and air to the rooms.

Back then, a major library typically had a big, central reading room at a distance from big, central stacks. But Main had 16 smaller reading rooms, each near relevant stacks with a combined 47 miles of shelves. It inherited and expanded the world’s biggest collection of chess materials and important collections of miniature books, folklore, Asian culture and history materials, and works about tobacco, architecture and baseball.

Eastman hired someone very different from herself to run Main: Marilla Waite Freeman, a vocal, bustling poet and lawyer from the Harvard Law School Library. Eastman was busy overseeing much more. She expanded Cleveland’s branch libraries to 28 and its school libraries to 30. She helped start the Cuyahoga County Public Library in 1924 and oversee the 10-branch system before retiring in 1938, six years before Cleveland Public spun it off.

The Great Depression led her to cut staff, wages and hours while patrons soared as high as 12,000 per day. “They’re turning to books because they have nothing else to do,” she told the Cleveland Press. “They tell us they will go crazy if they can’t get books to read.”

But the Depression helped Main when the Works Progress Administration funded beloved murals in Brett Memorial Hall of regional scenes.

The busy Eastman wished for more time to do what patrons did: read. She once wrote, “I’m a mere sampler of books, a sort of king’s taster!”

Her salary eventually rose to $9,000, or about $204,000 today. For two years, she asked the board to let her retire. She finally got her wish at age 71. She was given a farewell banquet with 2,000 guests at Euclid Avenue Baptist Church.

She won many honors, including the Cleveland Medal for Public Service. Charles Kennedy of the library board said her “creative, intelligent work along library lines has never been surpassed.” Vice Librarian Louise Prouty credited her with a rare “grasp of detail combined with a command of the whole.” Alfred Benesch of the Cleveland Board of Education praised “her deep humility — not the humility that doubts its own power, but the humility characterized by a curious feeling that greatness is not in the individual, but rather through the individual who sees something divine in all the children of men.”

In 1939, the city created Eastman Park next to Main. Twenty years later, Main took over the park, and volunteers began to turn it into the Eastman Reading Garden.

After retiring, Eastman lived almost 25 more years. Her legacy lives on today. The American Library Association named her as one of the 100 most influential librarians of the 20th century.

Chapter after chapter

After Eastman’s reign, Cleveland Public kept growing and innovating. In 1959, the old Plain Dealer building across the park became Main’s Business and Science Building, linked by a new tunnel. In 1997, Main replaced that building with the $65 million Louis Stokes Wing, 10 stories tall, containing 267,981 square feet and 30 miles of shelves.

Cleveland Public has gradually added movies, computers, databases, the pioneering FreeNet internet, podcasts, the first library loans of e-books, and many other up-to-date offerings. It’s in the middle of renovating or replacing all 27 branches. Main’s TechCentral space will reopen on Saturday with additions such as sewing machines, embroidery machines, a recording studio, and an ultraviolet printer.

Today Cleveland Public offers many programs, workshops, performances, clubs and other events. It lends meeting space to many organizations, such as Cleveland Housing Court and the Legal Aid Society. It offers safe space to patrons, especially children after school.

Cleveland Public now has 6.5 million physical or virtual items and employs 680 people. Per year, it makes about 6.3 million loans of materials, gets about 1.5 million visits, and spends about $66 million. It hosts the Ohio Center for the Book and the Ohio Library for the Blind and Print Disabled. It bills itself as “The People’s University.”

As part of Main’s centennial, the annual Cleveland Reads summer program has a theme this year of “100% Curious: Question, Explore, Discover.” Main is also showing silent movies from roughly a century ago on occasional Saturdays, including at 5 p.m. on June 21 and at 3 p.m. on July 12.

The new Library Shop at 424 Superior Ave. will be open 10:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Thursdays through Saturdays, highlighting the library’s collections and local creators.

In a press release, Felton Thomas Jr., who leads Cleveland Public Library, called the centennial “a vibrant tribute to how far the Library has come—as a place where culture, community, and creativity come alive. It’s a joyful reminder that imagination and learning belong to us all.”

Keep our local journalism accessible to all

Reader support is crucial as we continue to shed light on underreported neighborhoods in Cleveland. Will you become a monthly member to help us continue to produce news by, for, and with the community?

P.S. Did you like this story? Take our reader survey!