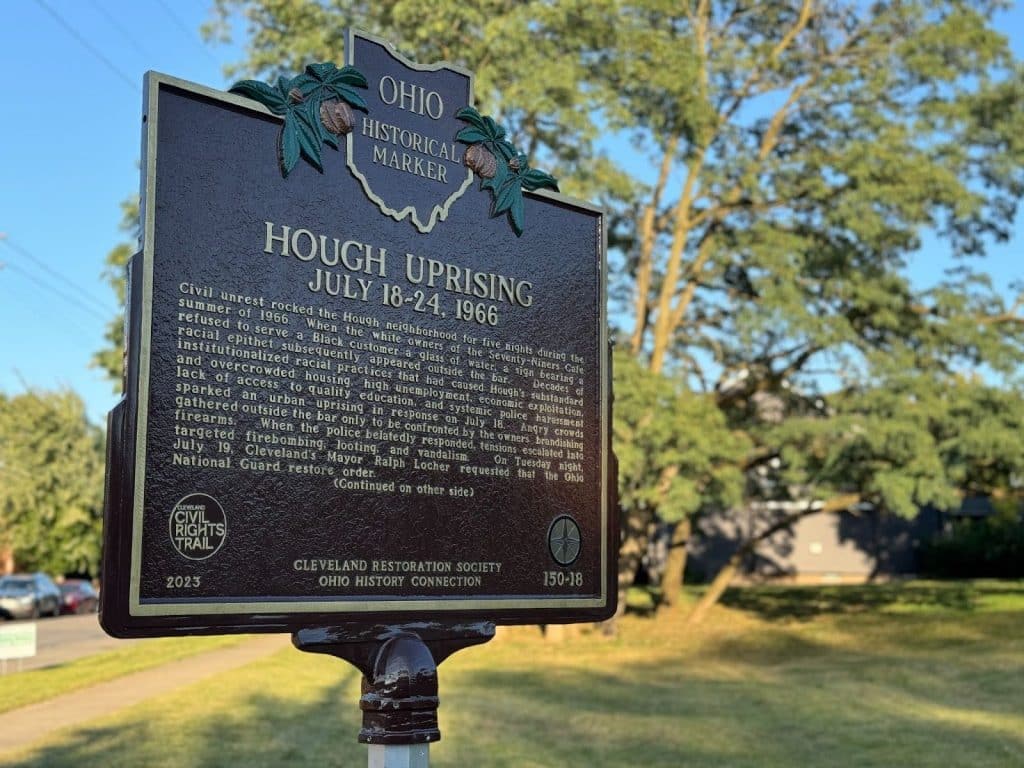

At the corner of East 79th Street and Hough Avenue, a grass lot is all that remains of the Seventy-Niners Café, the bar where the spark of the 1966 Hough Uprising was ignited. Fifty-eight years later, a new Cleveland Civil Rights Trail marker stands in its place, commemorating the uprising and its significance in Cleveland’s civil rights history.

The marker, placed by the Cleveland Restoration Society, a non-profit dedicated to preserving and protecting historic buildings and locations, serves as a reminder that the Hough Uprising was not just a response to a single incident, but rather to years of systemic racism, discrimination and social injustice.

“It’s our hope that by acknowledging the events that happened, that people learn from them, that we don’t repeat the issues that would have caused this type of event,” Margaret Lann, director of Preservation Services and Publications for the Cleveland Restoration Society, explained.

Cleveland Civil Rights Trail Expands

The Cleveland Civil Rights Trail project, led by the Cleveland Restoration Society, includes 11 historical markers across the city, each recognizing a significant location, person, or event in the fight for civil rights.

On Thursday, September 5th, the Cleveland Restoration Society unveiled the latest marker at East 79th Street and Hough Avenue, joined by elected officials, community organizations and residents. Like the other markers on the Cleveland Civil Rights Trail, the Hough Uprising marker resulted from a collaboration between the Cleveland Restoration Society, community members and scholars.

The decision to place the marker in Hough was made with the community in mind. Lann explained, “ Working with community engagement, we did all kinds of polls…and right away [Hough] was one of those places that rose to the top because it was a tragic event that left an imprint on a lot of people in Cleveland at the time.”

A Summer in 1966

The Cleveland Civil Rights Trail (CCRT) details the beginning of the Hough Uprising, which started on Monday, July 18th, 1966, when a Black patron at the Seventy-Niners Café was denied a glass of water. Tensions escalated when a sign with a racial epithet was posted outside the bar, drawing a crowd. The situation worsened with the arrival of police and reached a boiling point with the killing of Joyce Arnett, likely at the hands of police, according to the CCRT.

“Never did we think it would manifest into the kind of situation that it did, and it would be the kind of story that would captivate not only the city, the state, but the country,” recalled Dionne Thomas Carmichael, a Cleveland resident who lived on 79th St. and Central Ave. during the uprising.

For the next five days Hough was gripped by vandalism, looting, arson and gun violence. Case Western Reserve University’s Encyclopedia of Cleveland History estimates that the unrest caused an estimated $1 million to $2 million in property damage, left 30 people injured, saw hundreds arrested and resulted in the deaths of three more Black residents. As detailed in Marc E. Lackritz’s thesis, The Hough Riots of 1966, Percy Giles was reportedly killed in crossfire between police and suspected snipers, while Samuel Winchester, and Benoris Toney, were murdered by White assailants from outside of the Hough Community.

The roots of the uprising can be traced back before the inciting incident in the summer of 1966. As Hough experienced a rapid demographic shift to a predominantly Black neighborhood, it struggled with issues such as overcrowding, poor sanitation, inadequate schools, police harassment and predatory pricing in stores owned by individuals outside of the community.

“There were very real factors with racist lending practices and redlining that were occurring here and keeping people in neighborhoods that did not have housing and the public accommodations that everyone deserves,” Lann said.

Honoring the Past, Building a Better Future

For Carmichael, the marker is a powerful tool for educating future generations. “It’s a visible manifestation of what has occurred,” Carmichael said. “Sometimes we don’t relay this history to young people, that’s why this marker is important because people like me remember the riots but how do we relate that to younger people so they can understand what’s taking place in the world today?”

The Hough Uprising served as a catalyst for change in Cleveland. Initially a grand jury attributed the unrest to outside agitators despite a lack of evidence. Frustrated by this conclusion, the Hough community organized its own citizen grand jury to conduct an independent investigation. Led by future Congressman Louis Stokes, the investigation would go on to reveal that the deep neglect, abuse and disrespect Hough residents had long endured were the factors that fueled the uprising.

In the years that followed, efforts to rebuild Hough were spearheaded by community leaders like Councilwoman Fannie M. Lewis. Developments such as Lexington Village, Beacon Place and Church Square helped to revitalize parts of Hough. Decades after the unrest, Hough is still rebuilding, with plans underway to redevelop several properties into affordable housing and commercial space.

“The Community had to come together, they did not get the type of political response, at least not initially, that they were hoping for, but the community had to come together and rebuild for themselves,” Lann said .

Through a modern lens, the understanding of the Hough Uprising is evolving. Once labeled a “riot,” scholars, politicians and residents are now working to shift the narrative, highlighting the events’ root causes, emphasizing that the violence was not arbitrary, but a response from a long neglected and repressed community.

“This concept of terming it as an uprising came to light, and the scholars and our committee agreed that it was an appropriate term because the community was looking for political change. They were looking for change to their civil rights through legislation to make their living conditions better,” Lann said.

The legacy of the Hough Uprising reaches beyond its immediate aftermath. A year later, Carl Stokes was elected mayor of Cleveland, becoming the first African American mayor of a major U.S city. While the unrest highlighted racial inequities it also sparked a period of reflection and, while slow and hard fought, eventual change.

Among guest speakers at the commemoration event, Dr. Ronnie Dunn, the executive director of the Diversity Institute at Cleveland State University, emphasized the importance of how we remember this moment in history. “We must remember the Hough Uprising for what it was, a cry for justice, a demand for dignity and an urgent call for reform. It is a reminder that the road to equality is long but it is a road that we must continue to walk together.”

We're celebrating four years of amplifying resident voices from Cleveland's neighborhoods. Will you make a donation to keep our local journalism going?