Alongside longtime neighborhood resident, advocate and St. Matthew United Methodist Church trustee and chairperson Mittie Jordan, Hough inhabitants and church congregants have quietly spent the last decade building Brookdale Orchard into a bulwark against blight along Superior Avenue and Wade Park. The orchard’s supporters plan on replenishing abandoned acreage surrounding the Daniel E. Morgan K-8 School with gardens to build a food brand to serve an area that the City of Cleveland abandoned.

Mittie Imani Jordan makes a mountain of her roughly 5-foot, 7-inch frame as she traipses across the tiled floor inside a roomy main gathering hall toward a commercial kitchen, managing her crew like a sous chef. Around her, seven women sit or stand, poised above cutting boards and mixing bowls, rendering pears and onions into smaller chunks with the steady chop of knives and occasional clattering of peelers.

The dedicated women are spread out in the squat and unassuming St. Matthew United Methodist Church (St. Matthew), paring the produce of their labor into smaller morsels for salsas and jams. Jordan occasionally steps in to offer advice, raising her voice to a teacherly pitch as she addresses helpers in the same room where she can often be heard giving orders as chairperson or sometimes delivering sermons in her pastoral roles.

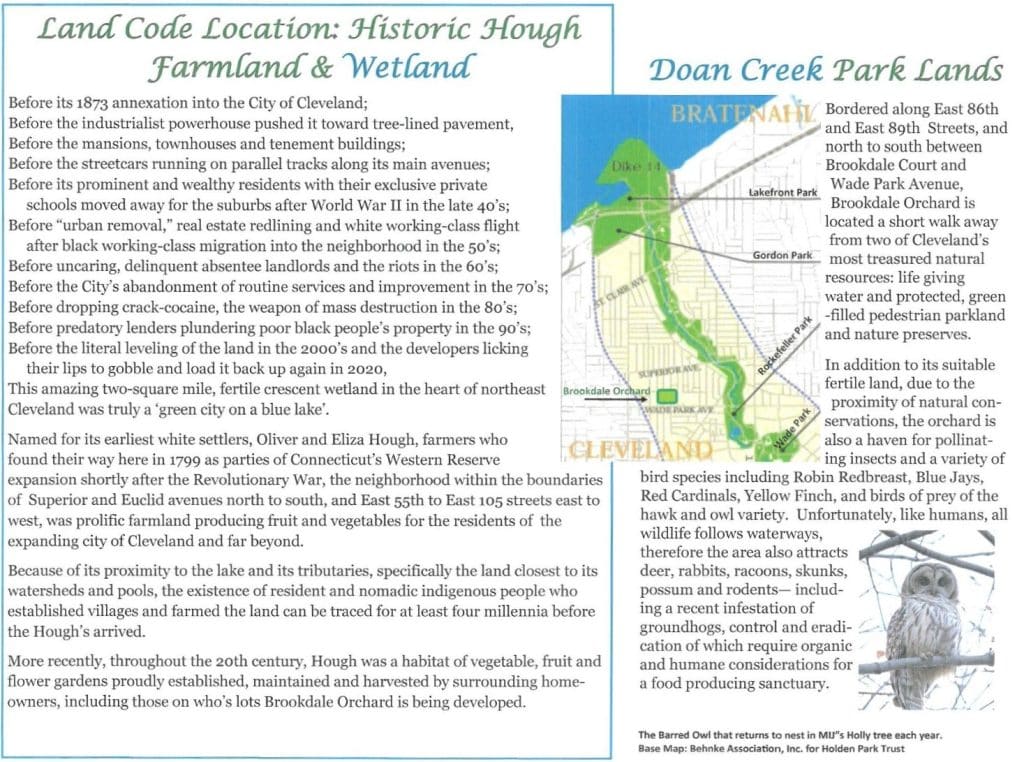

The building and its wraparound lot sit at 8601 Wade Park Ave., cornering the intersection where a one-way sliver of East 88th Street collides with Wade Park Avenue, placing it on the northeast margins of Cleveland’s Hough neighborhood. The area has been the subject of much local socioeconomic discourse. Jordan’s singular perspective on Hough started with her arrival at age 1 and her retelling of its history cuts through years of hardship like a thermal knife.

“My family’s been here for 71 of my 72 years,” she told The Land. “We were (among the) first wave of Black migration to Hough. It was a neighborhood that was working-class oriented; people took pride in their lawns and gardens … this was a very stable, family oriented community where people took pride. This is a place where we lived, we grew food together, we shared in that experience … and watching this neighborhood spiral into a war zone was unbearable…

“And I say that because, between 1953 and 2000, everything that hit us. It was one thing after another, starting with white flight, followed by Black class flight, followed by riots, followed by crack cocaine, followed by disinvestment from the city, followed by predatory lending, followed by property blimping — I mean just one thing after another.”

Jordan’s Hough childhood wasn’t idyllic; demographic changes caused racism to flourish on the streets north of Fairfax and Central and South of Glenville and St. Clair-Superior as in other areas of the city. In being one of the first Black families to arrive there, the Jordans faced many social barriers while attempting to navigate postwar economic drought alongside their neighbors.

To Jordan, who has lived there off and on since 1953, Hough is still home, but coming from her mouth, it sounds like the racial aversion she experienced in her formative years has morphed into something more sinister: poverty sustained by systemic racism. The pride that Hough neighbors once practiced fell by the wayside as the stores and restaurants closed, leaving a graveyard of abandoned homes that only posed greater profit opportunities for investors to buy, raze and either rehab or build upon as they fell into further disrepair.

Jordan describes the events as a sad arc for the neighborhood she’s dubbed “the best location in the best location in the nation,” positioning Hough as Cleveland’s crown jewel due to its single-mile proximity to the lakefront. The decades-long broadening of University Circle into a residential and educational population center caused developers and other stakeholders to divert attention from Hough as well as St. Clair-Superior to the north and Midtown to its south.

“They wanted this area to do what it did: Go all the way down to the bottom where the land is worth nothing,” Jordan said. “Get rid of the people and come in and take the land. That is the story over and over and over again all over the world.”

But not here.

A good foundation

The multicolored brick church finds itself endcapping a street brimming with hand-tended yards, well-maintained garden plots and fences that are noticeable against the abandoned structures typically found south of Superior Avenue between East 86th Street and East 89th Street.

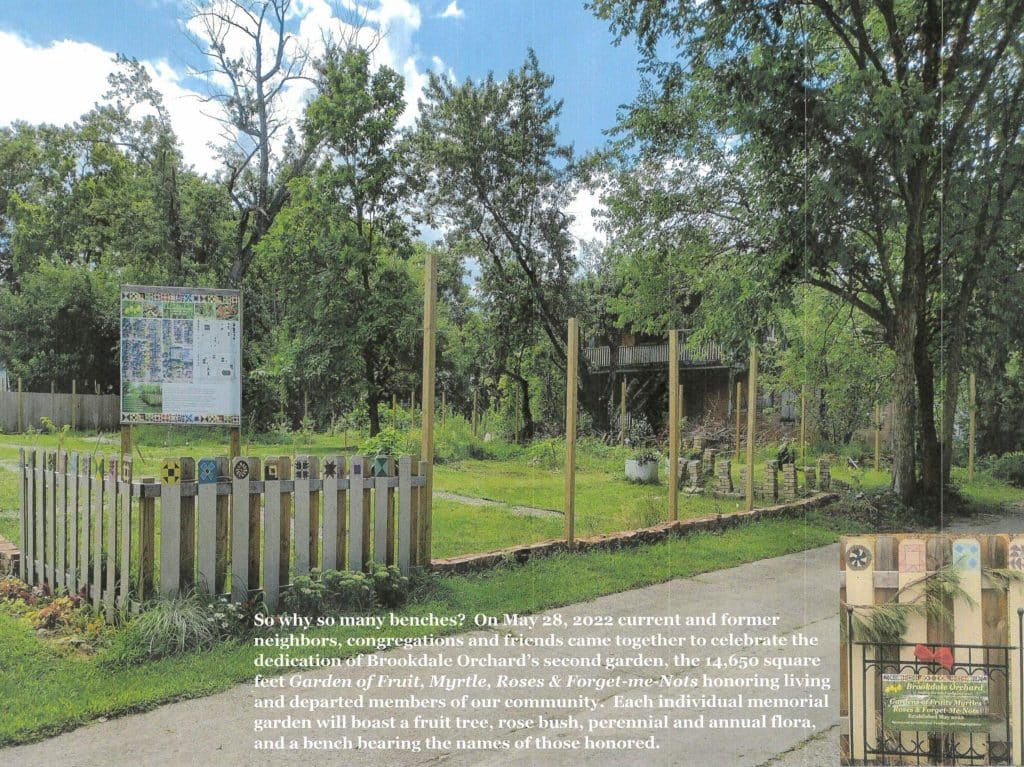

On fair weather days, pedestrians can be found traversing East 88th, often between the church and the few-block radius of a robust collection of garden plots visible from the playground outside Daniel E. Morgan K-8 School, a half-block north of the church. But the signs outside the plots do not bear Cleveland Metropolitan School District’s (CMSD) insignia; instead, they read “Brookdale Orchard … Sponsored by The Cuyahoga Land Reutilization Corporation.”

The block-spanning cluster of gardens presents a strange sight amid Hough’s general backdrop, until one connects the dots to realize that the church, school and orchard are inherently tethered. But, as becomes clear from speaking to Jordan and her allies, the toil being accomplished and documented there helps chart an important road map that could be used to uplift shattered communities recovering from systemic poverty; not just in Cleveland, but anywhere.

“You don’t mess with Mittie,” is an oft-uttered phrase from the mouths of residents encircling Brookdale Orchard. Whether credit belong to Mittie Jordan, St. Matthew or the Cuyahoga Land Bank (CLB) and Cleveland Land Bank for helping secure the land, it’s clear that these entities have combined into something that exceeds the value of their parts: a zone of safety and happiness, a pocket neighborhood and wider community that is divorced from the external politics that failed it for decades.

A solid plot

“(Mittie’s) a foot soldier if there ever was a person to be called one,” volunteer Ceco Selinas said during a break in paring pears inside the church’s gathering hall. “Strong feet and strong fists, too,” she laughed.

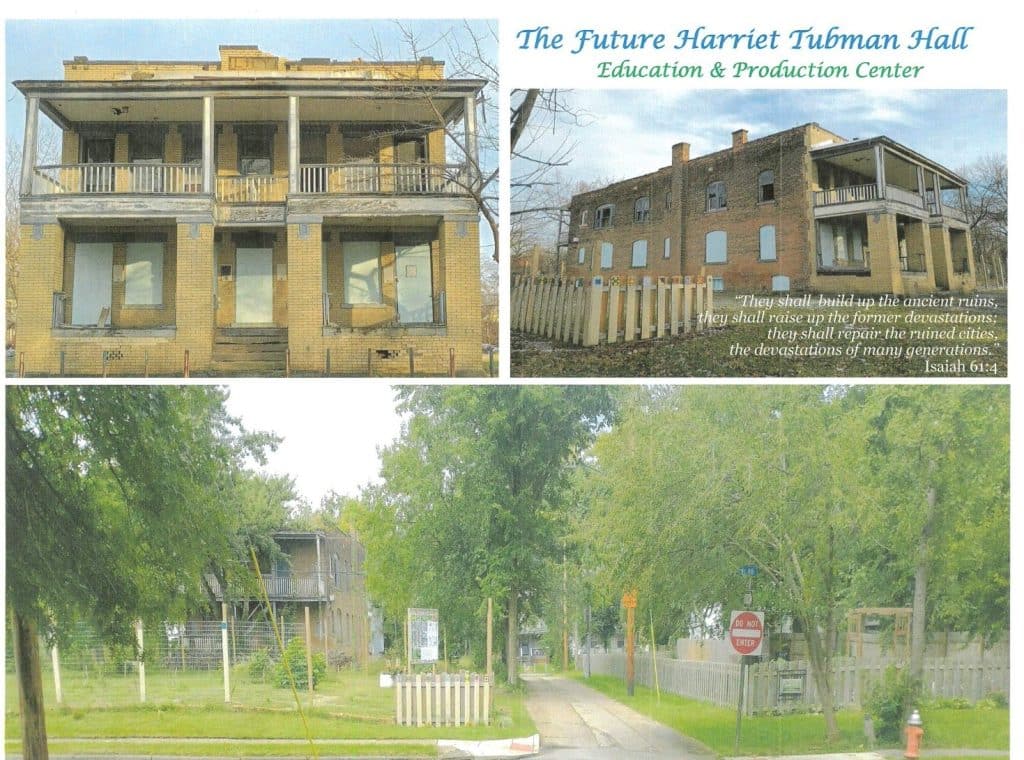

Jordan and her fellow congregants will spend the next few years upsizing from the Garden of Eden pear garden’s seven trees, having started with 50 sponsor-purchased fruit plants at Brookdale Orchard’s memorial gardens. Further CLB-aided acquisitions will provide more land to expand gardening and canning via Harriet Tubman Hall, which Jordan envisions as a hub of productivity for community members along Superior Avenue and Wade Park Avenue.

Helpers currently commit all their slicing, canning and other group work involving food out of the church’s main hall a half-block south of the pear garden. Once the abandoned building directly opposite the East 88th Street memorial garden has been renovated into the Tubman Hall education and production facility, it will eventually host such activities and classes to teach them to others from a more convenient location.

Both the garden and production facility help set the stage for the real kicker: the launch of the generational wealth-building Brookdale Orchard brands, entirely fueled by produce from the garden and laboring hands, including volunteer supporters. But, same as the community hall, don’t put a date on it.

Jordan intends for a proper hall opening and launch within the next few years but started working in early 2024 on funding campaigns to secure between $500,000 and $700,000 to restore the 6,600-square-foot building’s interior and exterior; the Cuyahoga Land Bank is keeping the building erect in the meantime. New additions to the construction will net new income streams for Brookdale Orchard in the form of a corner porch cafe, which will encourage those unfamiliar with the orchard to peek inside, and a greenhouse to expand growing seasons.

“The orchard is not my vision, granted,” Jordan explained while standing at the church amid the steady productivity of food preparation, work that will eventually take place at Tubman Hall. “It was the Lord’s gift to me as a vessel. But it made a lot of sense. If you grow the fruit and you sell the fruit, it’s a short-lived activity.“But, if you build a brand out of the fruit, then you’re talking about shelf life and talking about longevity wealth building.”

Jordan, a trustee, has learned from past experience that it’s best not to rush initiatives like Brookdale, which is sustained through many moving parts.

For an outsider new to the Brookdale Orchard scene — volunteer groups range in size, from a handful of children and teenagers accompanying Jordan on runs to retrieve supplies to the half-dozen women who picked pears to a 24-member summer work team — delineating which entities are responsible for what can be difficult.

Brookdale Orchard’s street address places it at the church, but the retrospect and prospectus booklet that Jordan distributes to seek civic funding also spotlights the Rockefeller Park Community Development Association, Inc., (RPCDA) another Jordan-founded initiative where she serves as chair.

The church owns the land on which the orchard is rooted, but RPCDA owns Brookdale Orchard as an entity and will redirect profits from the attached brand name into sustaining the garden and improving the community. The system is complicated, yes, but it’s managed to win the support of outside entities like the Cleveland Land Bank and Cuyahoga Land Bank while presenting a system of checks and balances to keep St. Matthew, Brookdale and RPCDA under one umbrella.

An unpacking of Jordan’s own history is necessary to understand the mettle and reasoning that continually compels the community powerhouse into investing her ingenuity and resources; East 88th Street hasn’t been her permanent home, but she’s certainly magnetized to it. Jordan has returned to the block where her family raised her through the mid-1970s multiple times between stints working in cultural and political roles for the City of Atlanta and City of Dallas

It’s worth noting that Hough has always been home in Jordan’s mind; she has returned to East 88th Street multiple times, whether to start and operate the now-defunct bookstore-slash-cultural outlet Deuteronomy 8:3 inside the Madison Building on East 105th Street for 14 years or to care for her ailing parents. Education and work are the only factors to remove her from Cleveland, but they couldn’t keep her away forever, and therein lie the keys to Jordan’s success: strategies are helpful, but they should also be flexible, lest they dilute an overall goal.

Plan, plan, plan

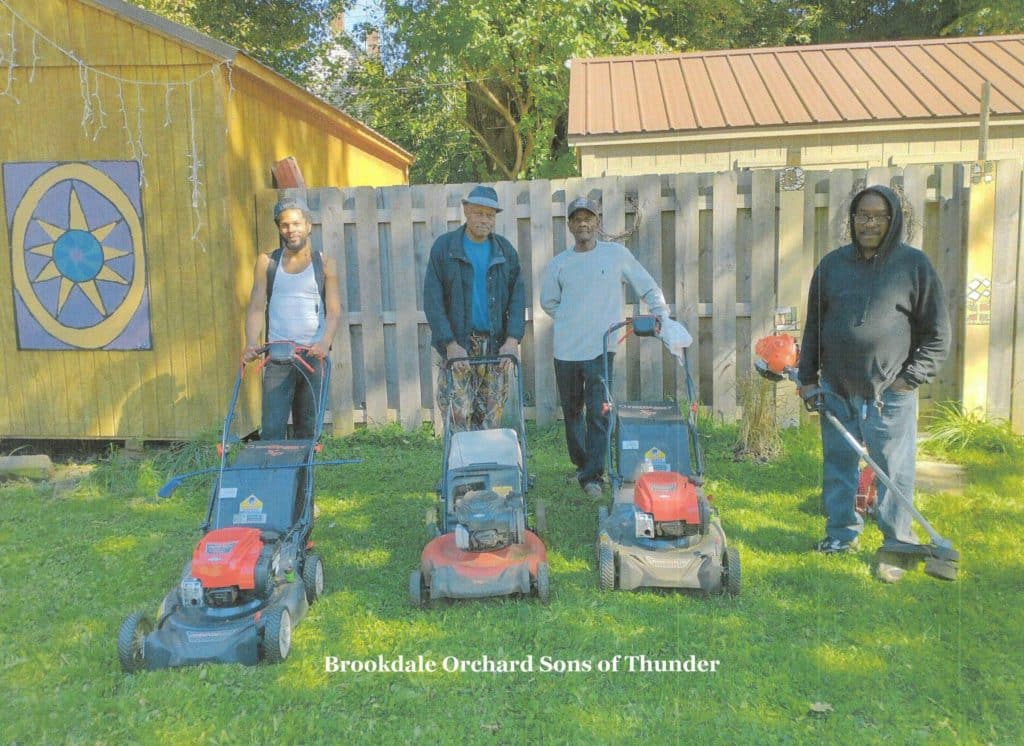

Jordan’s experience has taught her that the kind of work she intends to dirty her hands with comes at a measured pace; for now, the Daughters of the King and Sons of Thunder (respective titles for the women and men responsible for orchard maintenance) are knee-deep in building and maintaining gardens as well as community outreach.

St. Matthew has not made specific moves toward redeveloping other CLB land, including the Harriett Tubman Hall site, nor have Jordan and her peers charted a proper launch for the Brookdale Orchard brand, but Jordan gathered CMSD teachers and other community members throughout Brookdale’s network for a soft public launch on Aug. 31. Taking place across the street from the aforementioned 50-tree memorial garden, Brookdale Orchard’s Jammin’ for Jesus Harvest Festival doubled as a dedication ceremony to officially christen the Gus Frangos Daniel E. Morgan Wisdom Garden.

While kids frolicked in the grassy zone outside the school, adults gathered in the first of the orchard’s four planned wisdom gardens, so named for the STEM education opportunity the space provided for Daniel E. Morgan K-8 students spanning the sixth through eighth grades.

Between April and October 2023, CMSD personnel led students in measuring, designing, building and installing the raised beds and fencing that now pen in nearly 5,800 square feet of growing and gathering space. The church intends to initiate educational programming on garden-building, cultivation, as developed by Jordan and other members of Brookdale Orchard’s 18-person board of directors, sometime this fall.

Further initiatives like Tubman Hall and the brand launch will crystallize in time, as the St. Matthew congregant has learned the pitfalls of progressive-oriented planning are at least partially responsible for the social and economic corrosion her neighborhood has faced. While dozens of Hough residents sustain efforts at the church and development association, Jordan clearly sits poised at the center, leveraging lessons from her 72 years to inspire energy among the orchard’s supporters.

“I would describe Mittie as a powerhouse, a fireball,” Elgan Reynolds, former head pastor at Shoregate UMC and lifelong St. Matthew congregant, said prior to the dedication ceremony. “She’s got more energy than any four people I know, especially when something stirs her passion. And this has stirred her passion.”

To hear Jordan say it, her corner of Hough manifested the neighborhood’s worst side — guns, prostitution, drug trafficking and general violence — prior to her involvement. Against the backdrop of the Daniel E. Morgan School and the former John W. Raper Elementary School, plus numerous religious and cultural hubs, Hough’s maze of abandoned buildings stood out as visible blight when viewed among the surrounding University Circle, Asiatown and Fairfax neighborhoods.

Jordan started galvanizing community interest into the orchard in 2011, when the pitfalls of planning became apparent to her neighbors and fellow church congregants upon realizing that the blocks immediately surrounding them contained over 100 vacant housing structures. While the Wade Park-Superior region wasn’t the only area suffering due to hollowed homes at the time, it seemed to be the only one that lacked outside commitment to help fix it.

“When it was clear that we had been completely abandoned, neighbors and my congregation at St. Matthew Church pulled together and looked at what we are, who we are, and where we are,” Jordan said.

Tracing the neighborhood’s worst issues to the abandoned buildings, Jordan used education and volunteer experience gleaned from her time at Massachussetts’s Smith College to form the Rockefeller Park Community Development Association, which owns Brookdale Orchard as a brand. The orchard initiative later formed its own 18-member board of directors, including Jordan, who made executive decisions about programming, placement and goals for the gardens.

The Rockefeller Park redevelopment association’s members, first consisting primarily of area residents and St. Matthew’s congregants, worked under Jordan’s leadership to launch their initiative and make their presence felt. They sent concerned letters to Cleveland City Council members and department heads while Jordan held presentations with other officials. Initial outreach and stabilization efforts netted the attention of Cuyahoga Land Bank founder Gus Frangos, who recognized Jordan’s vision and helped place the properties in the hands of people who would use them.

While Jordan’s orbit already includes some several-dozen helpers and advocates who assist with general church- and neighborhood-wide efforts in collaboration with St. Matthew and Brookdale Orchard, she also realizes outside assistance can diminish problems that would otherwise be overwhelming.

Enter the CLB and Frangos, who, according to Jordan, worked up until the time of his death in August to hold land owners accountable to aid projects like hers. Whereas Jordan was unable to track down the property owners who kept erect the structures plaguing her neighborhood, Frangos and the city land bank used their administrative processes to obtain contact information and then interfaced with local, state and federal agencies to secure land parcels for Brookdale’s use.

Between the City of Cleveland’s land bank and Cuyahoga County’s efforts, Brookdale has been able to annex over 30 parcels holding four distinct gardens and hundreds of budding fruit plants.

“My dad had this creative mind where, if he understood your vision, he could see a future where it existed, and his objective up to that point was to make it happen,” John Frangos, the late CLB founder’s son, explained.

The younger Frangos, now working as a software developer, recalled discussions with his father, who previously served on Cleveland City Council and as a Cleveland Municipal Court magistrate, in which he spoke to him about working to acquire Brookdale land.

The work earned Frangos a memorial spot in the garden’s name alongside Daniel E. Morgan, another former city council member and Cleveland’s last city manager (Cleveland switched to a mayoral government in 1931). Frangos’ work focused on the municipality’s neighborhoods in his political work. But Brookdale’s focus on history and honor, as evinced by the names attached to the gardens and the Codes to Freedom adorning their fences, also highlight Brookdale’s broader appeal. It’s a project, one comes to understand, that could be adapted to benefit many places, not just Cleveland or Hough.

In studying the orchard and its history at the ground level, one realizes it’s not just a penned-in collection of soil plots, floating detached from time and place. It, like anything else, is a part of the Earth and is inherently tied to people and ideas that existed long before its inception.

Need and greed

On an extremely personal note, my take is that Mittie Jordan’s work with the Brookdale Orchard and within the St. Matthew community casts a piercing glare on the relationship between religion and need, following the footsteps of other Hough pioneers with similar intents. Having grown up tasting the suburban flavor of the Catholic Church (I hail from a Western Pennsylvania town where the roughly 33,000 residents haul in an average median income of $120,000 annually), I developed an ambivalence to the concept of religion as a healer. I prepped meals at soup kitchens and knew friends who attended mission trips as well as pastors who ruminated on the plights of the poor during sermons.

But it wasn’t until I became an adult, moved to Cleveland and became immersed in this city’s particular blend of history, culture and poverty that I came to understand the reality of need. And it wasn’t until I started profiling Mittie and telling her story that I came to a striking conclusion: organized faith is important and can be a powerful problem solver.

The neoliberal, nonprofit-based approach to wrong-righting that the average community development agency takes can be effective, as Northeast Ohio residents have seen not-for-profit entities advocate for important issues without falling victim to the traditional power structures that tend to adulterate good intentions.

But shifting any amount of money around – employihng the same tactics as a private business, essentially – can only push an issue so far. Boards turn over, mid-level management and administrators shuffle around; goals and mission statements become adulterated as LinkedIn bios get updated.

Charitable conglomerates also have the tendency to operate like funnels, often shifting funds from various sources into a single stream (a 2022 report on the state of Cuyahoga County’s nonprofits, the United Way of Greater Cleveland found that only 2% of local nonprofits were responsible for controlling 93% of nonprofit assets in the region). It’s a top-heavy practice that invariably grants more resources to larger, front-facing, publicly oriented charities than the ones that get less press.

It’s a good thing, then, that someone with the passion and intent that Jordan carries is married to Brookdale, and not just because she lives on the street. She’s wed her soul and intent to the place, and in so doing has budded the passions of other volunteers who will sustain it when she is no longer able to do so. Might Brookdale Orchard falter or fail someday? Hopefully not, but time immemorial has shown that no organization is bulletproof.

This is where Jordan’s initiative, to me, unfurls into a much larger blueprint for the mind and for the city. It wasn’t until I started profiling Mittie and telling her story that I realized, one, that I had missed a very important lesson about religion and, two, so has everyone else, seemingly. Jordan’s approach does not leave anyone out and does not sideline a single community member regardless of ability, and it does so while eschewing hundreds of years of political custom and backwards problem solving.

With farming and religion comprising Brookdale Orchard’s core, the gardening initiative positions the age-old solutions of food and faith as a dual panacea for modern human suffering. Long before store shelves were populated with self-help books, millennia before community development corporations chartered themselves into existence, people were digging in the dirt to grow food and contemplating a higher power. Both of those activities are not only costless, but – if practiced and monitored humanely – they fail to harm the environment or the human psyche.

Church members and Brookdale helpers who have disabilities aren’t sidelined for efficiency’s sake; they have the liberty to engage with orchard work in whatever capacity they can. Children, if interested, are gifted the reins of experience to cultivate the Brookddale soil as some congregants age out of the toil.

While the sustained efforts of St. Matthew attendees, RPCDA members and Clevelanders inside and outside of Hough deserve ample credit for the bushels of fruit currently gestating on Brookdale Orchard’s branches, it was Jordan who mobilized that work in the first place. And it’s clear that Jordan’s lifestyle — her words, her actions, the people and places with which she spends her time, the name of her former bookstore — reference and underpin her faith.

Bible passages share room with quotations from authors and playwrights in the pages of the prospectus Jordan distributes; each garden in the orchard has been mindfully named after biblical motifs or concepts; the people who help her maintain them all converse politely and with reverence for one another. It’s just not the kind of behavior you see when people are grinding away at “real jobs,” making “real money” with “real stakes.”

Odds are, if Jordan had been born with the same potent seeds of intelligence and willpower she eventually nurtured, but had been brought up under different conditions or in a secular household, things would be much worse for everyone but her. The land surrounding Brookdale Court would still be a maze of dead trees and undergrowth, East 88th Street would remain clogged with detritus and the Hough residents who have returned the neighborhood to its legacy of gardening wouldn’t have their hands in the dirt.

Jordan, meanwhile, would probably be sitting on a decent stack of retirement earnings after a several-decade career of 9-5 work, quite possibly having stuck around in Dallas or Atlanta or, even, upscaling to one of the high-rise apartment buildings Downtown.

But there’s a duty there, a sense that Jordan would be restless and unhappy if she weren’t blazing her current trail and instead succumbed to creature comforts. The 72-year-old possesses a warm yearning and sense of obligation that has rendered Brookdale Orchard in her mind as not merely the best solution to the plight of poverty and the cycle of colonialism that hinder real cultural and emotional progress, but the only fix that won’t make things worse.

Is living in a skyscraper downtown or a nice Lakewood-adjacent loft or a house built for four in Cleveland Heights comfortable and good? Absolutely. But it requires a high degree of cognitive dissonance to enjoy that lifestyle while ignoring the five square miles of Cleveland blanketed in dead weeds, broken glass and crumbling houses.

The relationship between piety and philanthropy is a well-noticed and much documented one, but I believe sharing Mittie Jordan’s story can serve as a restorative tonic to anyone, anywhere. Yes, it takes effort, time, sweat, pain, cursing and maybe even a little shifting of one’s brain and beliefs to get there, but real change and real healing are both possible without having to employ a costly team of political scientists to half-solve the issue over years of planning.

It’s not something that everyone will see; many will outright dislike the social structure that Jordan is building, but for anyone that visits Brookdale Orchard for themselves, the lessons are splayed out as clear as the rows of pear and apple trees. Tracy Hill, CMSD’s executive director of family and community engagement, summed it up perfectly while calling upon memories of Mittie from time they spent living in Oberlin College’s Afrikan Heritage House:

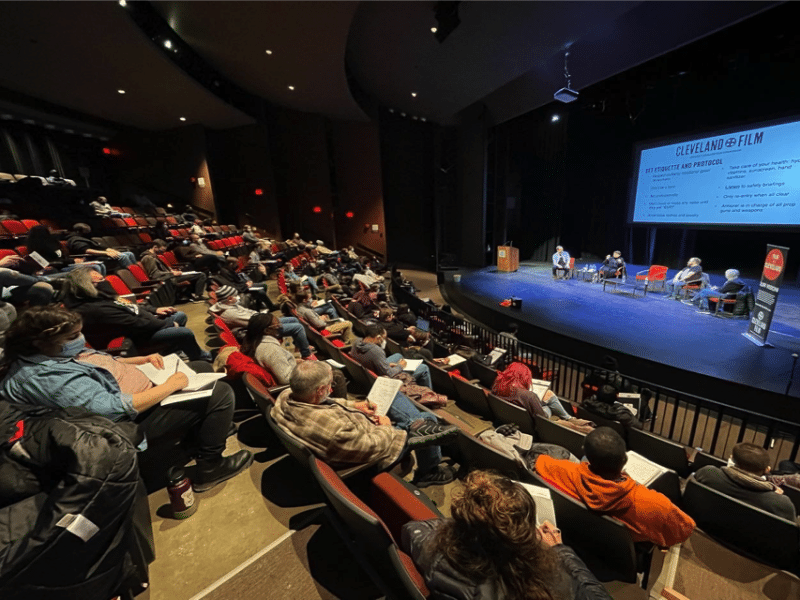

“Mittie transformed the neighborhood that she grew up in,” Hill told an audience of over 100 people at the late August garden dedication ceremony. “She also helped transform my life… She brought to all of us the healing energy, the consciousness, the faith.”

Readers can contact Jordan and/or Brookdale Orchard via 216-288-9759 or gardener@brookdaleorchard.org or follow the orchard’s Facebook page for updates.

Those interested can glean more information on formative Cleveland politics during the time of Jordan’s upbringing from Leonard N. Moore’s 2002 treatise “Carl B. Stokes and the Rise of Black Political Power.” More can be learned about inciting incidents in the Hough neighborhood via Mark Lackritz’s 1968 book, “The Hough Riots of 1966.”

The Cuyahoga Land Bank and Cleveland Land Bank accept applications for land reutilization initiatives depending on scope and purpose throughout the year.

Keep our local journalism accessible to all

Reader support is crucial as we continue to shed light on underreported neighborhoods in Cleveland. Will you become a monthly member to help us continue to produce news by, for, and with the community?

P.S. Did you like this story? Take our reader survey!