With literacy rates plunging across the U.S., Ohio last year became one of 30 states to require teachers to use the Science of Reading in the classroom. Learning to read by reading is out; phonics-heavy direct instruction is in. But Lakewood schools hadn’t waited for the state mandate to begin making changes. They were already starting to align their teaching methods with the Science of Reading before the state law went into effect in 2024. Two years later, what are the results?

The statistics are painful: 40% of American fourth graders in 2024 were reading at “below basic” levels, the most in 20 years. So said the National Assessment of Educational Progress, sometimes called the “nation’s report card.” Third graders at “below basic” reading levels lack the foundational skills needed for success in future education. When the emphasis shifts from “learning to read” to “reading to learn,” they fall further and further behind. The results persist into college and beyond. There are students at elite colleges, claimed Rose Horowitz, in The Atlantic, who arrive never having read a book cover to cover, and they refuse to start reading in college. This is more than COVID-19 learning loss; studies show that reading skills were weak before COVID. Some blame standardized testing, others, increased rates of school absences or ubiquitous cell phones. But the cause may lie elsewhere – in reading classrooms themselves

For years, children were taught to read with methods based on theories called “reading recovery” and “balanced literacy.” Children explored reading and writing, using classroom libraries of “leveled books” purchased from the educational publisher Heinemann, in a comfortable, supportive setting, according to reporting from American Public Media. The teacher intervened, if necessary, to encourage students or supply on the spot instruction. But since children learn best by doing, it was thought, understanding sentences and words would develop naturally through interaction with books. When they came to a word they didn’t know, children were taught strategies to guess its meaning, using a method often called “three-cuing,” and told to “sound out” words only as a last resort.

However, in-depth investigative reporting from American Public Media, published as “Sold a Story,” finds deep flaws in these methods; in fact, it is claimed they are ineffective with about 60% of students. The reason, according to cognitive scientists cited in “Sold a Story,”, is that while children’s brains are naturally wired to pick up the languages they hear spoken around them, most children cannot just “pick up” how to read and write through exposure to books. To become proficient, they need structured instruction, repetition, and practice provided by the teacher to construct the neural pathways linking sounds with letters and words.

“Sold a Story’s” impact led legislatures in around 40 states (as of this writing), including Ohio, to mandate teaching methods validated by what is called the “science of reading.” Lakewood schools, however, did not wait for the state. According to Steven Ast, director of teaching and learning for the district, “We had actually been working with our team on shifting back to more science of reading approaches for teaching reading prior to the state’s mandates.”

I sat down recently with Ast to find out why, and learn more about the changes Lakewood has made.

Science of Reading in Lakewood

Ast came to Lakewood with experience in high school education, as a teacher, then a principal at Chagrin Falls, and then Broadview Heights. “As I took this position,” he said, “I was learning a lot about elementary education, and, probably most importantly, how kids learn to read. There was a lot of news coverage, a lot of books being released, the State of Ohio had started doing Professional Learning Series on the science of reading, what research was telling us about how the brain processes learning, how those neural pathways start getting connected, what parts of the brain are activated. Basically, research is telling us it’s really important to have very explicit phonics instruction, being very specific with students about … these letters represent these sounds, or these groups of letters represent these sounds.”

As Ast was learning and making changes during this period, so was everyone else. First, the Lakewood Elementary Education Coordinator offered professional development to teachers in aligning practices with the science of reading.

“Then, toward the end of that year, we started getting information from the state about their legislation. At that point, it was about dyslexia. So our kindergarten, first, second and third grade teachers, along with their intervention specialist, had to complete a dyslexia professional learning module. And then shortly after that … the state required all teachers, pre-K to 12th grade, to complete science of reading modules … New curriculum materials had to be adopted. There were some specific requirements about what kind of curriculum materials you could have for English Language Arts, what kind of phonics program you could use,” Ast said.

But there is much more to a science of reading-aligned curriculum than phonics. Take “phonemic awareness,” for example, an important part of the new curriculum. Phonemes are the sounds a particular language uses in speech. They are what make up spoken words, and they differ from language to language. Phonemic awareness means becoming aware of the sounds you make as you speak a language, a necessary step if you are to learn to connect those sounds to letters. Multilingual learners must take an additional step if they are still learning the sounds of spoken English, and in the Lakewood schools there are about 300 multilingual learners, speaking 29 languages.

“So, in addition to the classroom teacher, we have individual, small group instructors, licensed teachers, that serve each of our elementary schools, supporting our multilingual learners,” Ast said.

Or consider that, to the “science of reading,” language comprehension is considered to be as important as “decoding,” or translating written words into spoken word To succeed at reading, it is not enough to sound out words. Students must understand what the words mean, Vocabulary plays a role in language comprehension, and so does background knowledge; however research is still disentangling their relationship.

Impact and response

How have Lakewood teachers responded to all these changes? There were, Ast said, “Some teachers that had been teaching longer, that had experience with those very phonics-focused approaches. And then we had teachers that probably did their pre-service training in settings with the balanced literacy approach.” With time, Ast said, “Teachers have come to the realization that, hey, this is rooted in research, it’s research-based. And then, in personal experience, working with kids, they see that it works… I feel like our teachers are more focused on getting the best results for our kids and doing right by kids.”

Students are also responding well to the changes. The new curricular materials “have rich content with lots of vocabulary. Student feedback has been very positive and the students have found the units very interesting. Lakewood’s assessments of student reading development are showing positive outcomes with fewer students needing intervention,” said Ast.

Still, despite the new direction in reading instruction, Ast retains a good bit of respect for “balanced literacy” approaches. “I had the opportunity to attend a professional learning session that was led by the Teachers College [Columbia University] team with strategies from that program were very sound … the way that they designed lessons, the way that they provided students some voice and choice, the methodology of talking with the students about the reading. But it was lacking a very strong, very intentional framework for kids to learn phonics. Once we were aware that the phonics unit of study from the Teachers College program wasn’t doing what it needed to do, we moved away from it.”

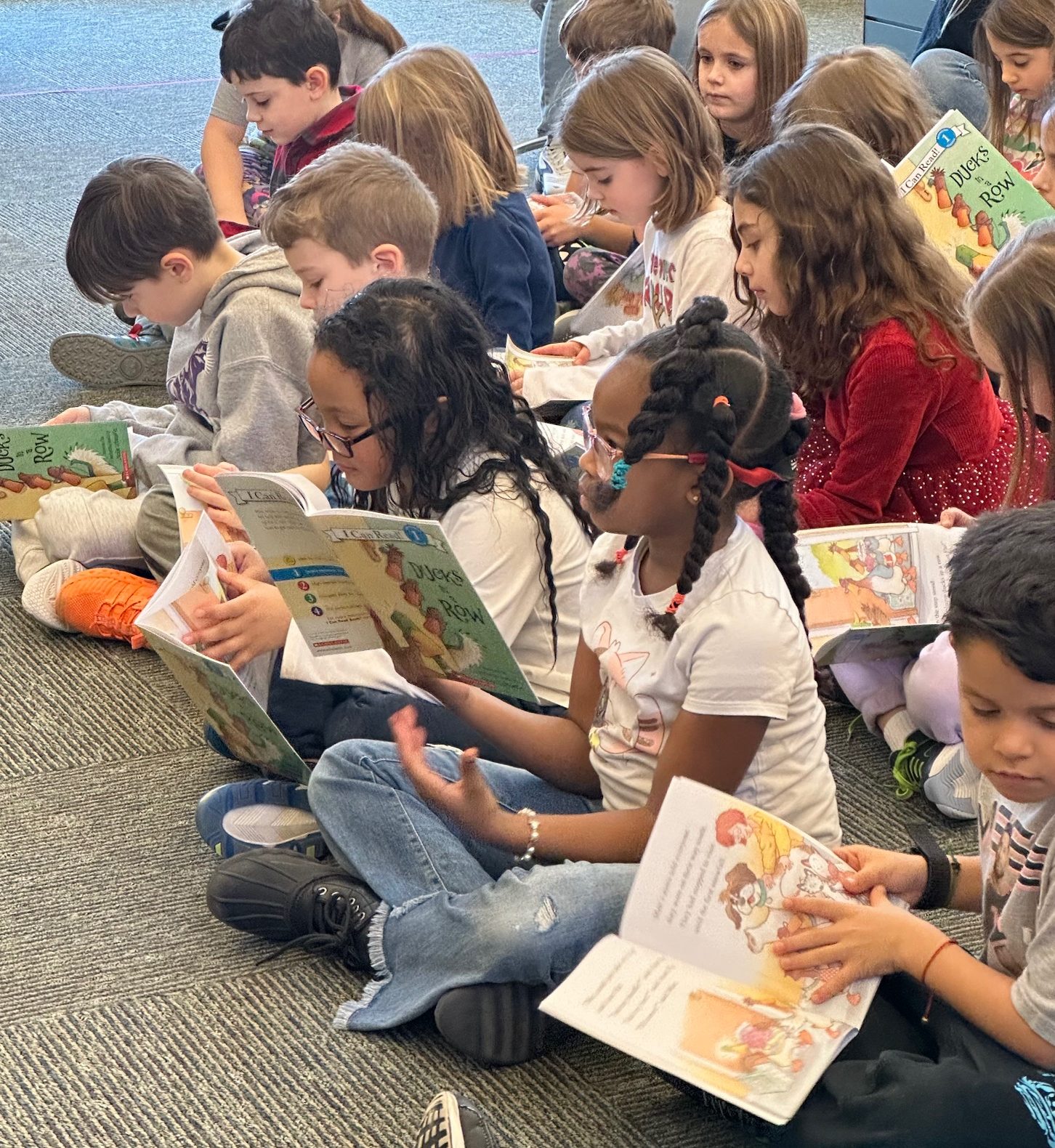

Ast added that, “At the end of the day, we need to make sure that they have those routine, process-oriented approaches to reading and sounding out words and making sure that they can decode the text.” But, “We still want kids to be excited about reading, to love reading, we still want to do all those extra things with students so that they love to read.”

It should go without saying that implementing an entirely new curriculum, including new textbooks, new assessments, and extensive professional development for teachers, takes money. What revenue streams have been available for Lakewood? “We leveraged ESSER funding [COVID recovery funds] and district funds. The State of Ohio provided some funding to districts this past year, based on what you had or still needed to adopt, but the state dollars were not enough to cover all the expenses related to these changes,” Ast said, adding, “The state has not indicated a plan to further support school districts’ implementation of ‘science of reading’ based instruction.”

Now vetoed provisions of the state budget bill would have made it still more difficult for school districts in the future. House Bill 96, the budget bill, sought to cap school district reserves at 30% of the previous year’s expenses. (The Senate version would have capped reserves at 50%.) School administrators said that the caps, in effect, would force them into poor financial management practices, making them “live paycheck to paycheck” rather than saving for future contingencies such as higher than expected inflation. Given the high costs of the “science of reading” state mandate, and the potential for other costly state mandates to come, schools would have to dig deep into their local funding pockets and try to pass more frequent levies.

Asked for a comment, prior to the vetoing of the provisions, District 13 State Rep. Tristan Rader (D), replied: “Capping school district reserves — first at 30%, now bumped to 50% in the Senate — is a reckless policy masquerading as fiscal responsibility. Strategic reserves exist for a reason: to weather cost spikes, invest in mandates like the science of reading, and avoid constant trips to the ballot. This bill punishes good planning and undermines financial stability. When the state mandates sweeping curriculum changes like the shift to the science of reading, it should also provide full and sustained funding — not just a one-time grant or temporary federal relief. Instead, HB 96 kneecaps districts like Lakewood by forcing them to spend down their rainy-day funds just to keep up. That’s not responsible governance; it’s sabotage.”

Sadly, Ast sees these state actions as a trend. “Recently, Ohio legislators have been more focused on sending public dollars to charter and private schools through vouchers and funding mechanisms,” he said. “So I am not expecting the state to provide too much support to our neighborhood schools in general. These are stories that need to be told!”

Gov. Mike DeWine vetoed the state budget bill’s caps on school district reserves in July. According to Signal Statewide, DeWine explained his veto, arguing, “While seeking periodic taxpayer approval of levies is appropriate, this item is contrary to local control and will undermine efforts by school districts to manage their finances responsibly and follow best business practices. Further, the increased levy cycle could cause more levies to fail due to levy fatigue, impacting the overall financial stability of school districts. Therefore, a veto of this item is in the public interest.”

We're celebrating four years of amplifying resident voices from Cleveland's neighborhoods. Will you make a donation to keep our local journalism going?